London Punk 40 years on – misguided anarchy but effective in telling the Tory elite where to get off

2016 marks 40 years since punk rock became an official safety pin movement in Britain after “Year Zero” was declared and a music revolution began, according to the media.

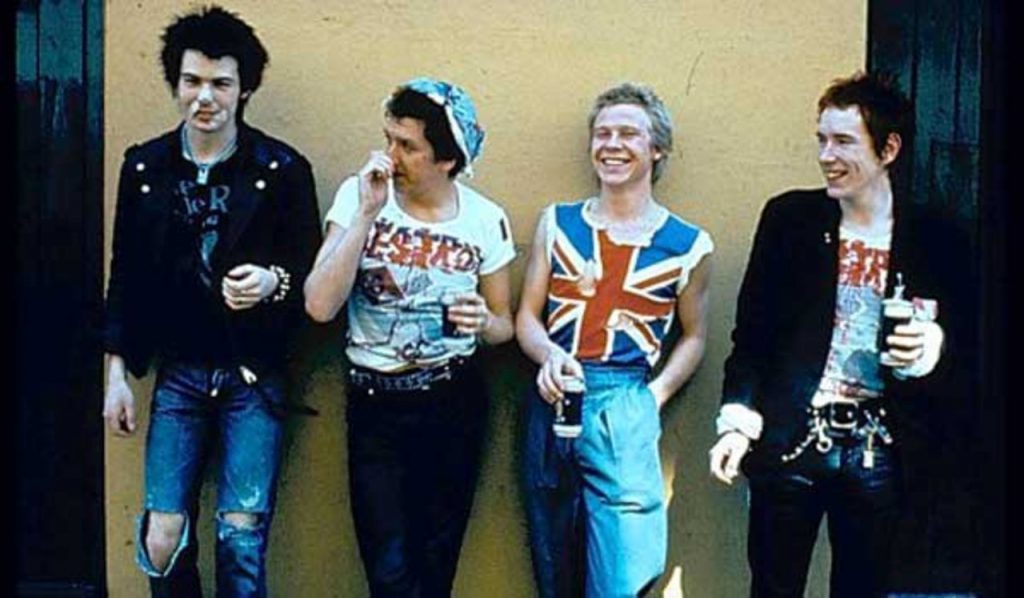

The Sex Pistols were a catalyst for the punk movement from Britain

The Sex Pistols were a catalyst for the punk movement from Britain

Niall Ferguson, Professor of History at Harvard writes:

”On February 12, 1976 one of punk’s leading protagonists the Sex Pistols performed their break through gig at the Marquee club in London. To celebrate the anniversary Matthew Butson, Vice President of Getty Images Archive has collated a series of photographs from over 90 million historic images held in their archive.

In a famous footnote, that least Tory of historians A.J.P. Taylor famously called Winston Churchill “the savior of his country.” Few of my generation of historians would agree with me when I echo him in calling Margaret Thatcher the savior of her country. But she was — and her legion of left-wing academic critics were just part of what she attempted to save Britain from.

It is easy to forget what Britain was like when Margaret Thatcher became prime minister in May 1979. I was 15 years old and the best way to describe myself at that time is as a punk Tory.

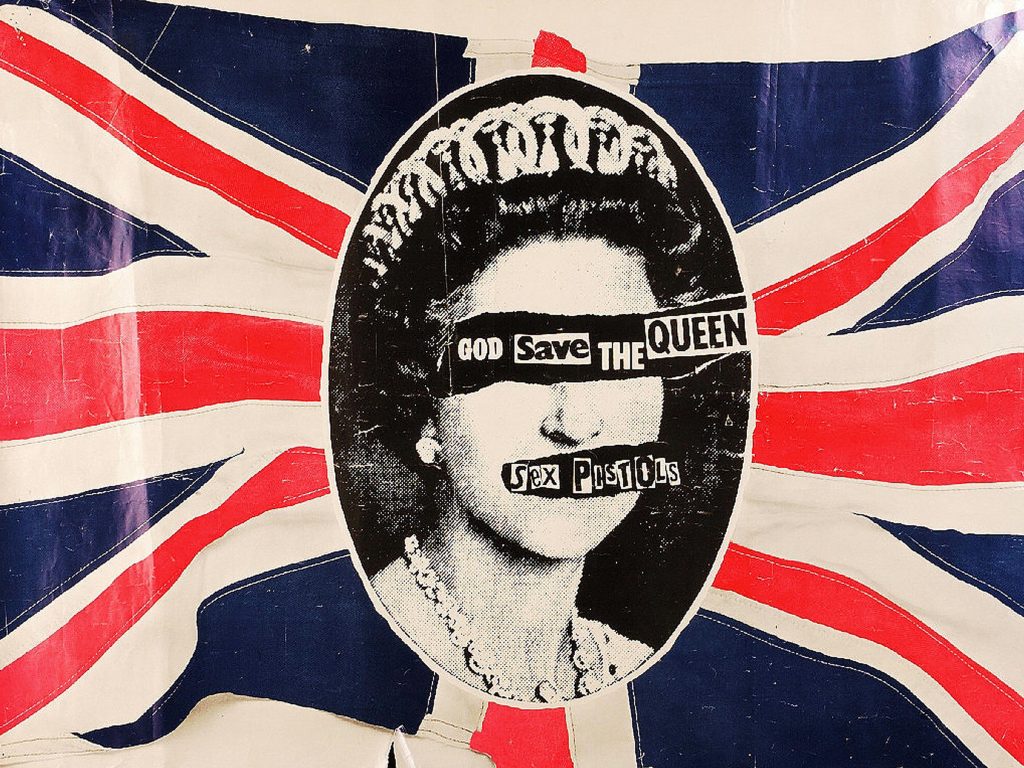

I was punk in the sense that my teenage soul had been set ablaze by the Sex Pistols’ incendiary single “Anarchy in the U.K.,” released not long after Thatcher had become the Tory leader, and by their inglorious “God Save the Queen,” spoof which followed soon after:

“God save the queen

The fascist regime

They made you a moron

Potential H-bomb.

God save the queen

She ain’t no human being

There is no future

In England’s dreaming.”

What made me and my friends leap around like lunatics to those words, snarled by the pallid degenerate Johnny Rotten, was an intense frustration. We didn’t for a moment think the queen was a fascist or inhuman.

What made me and my friends leap around like lunatics to those words, snarled by the pallid degenerate Johnny Rotten, was an intense frustration. We didn’t for a moment think the queen was a fascist or inhuman.

We were just utterly and completely fed up with post-war, post-Empire, post-Beatles Britain. In the late 70s, there really did seem to be “no future / in England’s dreaming.”

Nothing worked. The trains were always late. The pay phones were always broken (where I lived, they were mainly used as urinals). The first letter I ever wrote to a newspaper was to complain about the exploding price of school shoes. And worst of all were the recurrent strikes. Strikes by coal miners. Strikes by dockers. Strikes by printers. Strikes by refuse collectors. Strikes even by gravediggers!

Consider this. In the single month of September 1979, as the trade unions sought to undermine the newly elected Conservative government, the number of days lost to industrial action was nearly 12 million. (Last September it was 8,000.) The inflation rate in September 1979 was just under 17 per cent — down from its peak, four years previously, at over 25 percent.

So I was a punk out of frustration. But I was a Tory out of hope. In “Time for Truth,” another punk band of the time, The Jam, had the honesty openly to blame the Labour Party: “I think it’s time for truth / And the truth is you’ve lost, Uncle Jimmy” — an unmistakable reference to the avuncular Labour Prime Minister James Callaghan, whom Thatcher ousted in the 1979 election. Callaghan — whose nickname “Sunny Jim” became a bad joke in the 1978-79 “Winter of Discontent” — made our hearts sink.

On Jan. 10, 1979, on his return from an economic summit held on the sunny Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, Callaghan was asked by a journalist, “What is your general approach, in view of the mounting chaos in the country at the moment?” Callaghan gave the kind of mealy-mouthed, patronizing answer we were sick of hearing from politicians:

“Well, that’s a judgment that you are making. I promise you that if you look at it from outside, and perhaps you’re taking rather a parochial view at the moment, I don’t think that other people in the world would share the view that there is mounting chaos.”

At the end of the conference, Callaghan joked that he doubted he would “even find a cup of coffee” if there was such mounting chaos. (Sure, we had coffee at airports in 1979 — disgusting instant stuff.) This show of insouciance did not go down well with the British press. The front page of the following day’s Sun newspaper bore the headline: “CRISIS? WHAT CRISIS?”

By contrast, Thatcher — rather to our surprise, it must be said — gave us hope. And part of the reason was her refusal to give answers like Callaghan’s. “My job is to stop Britain going red,” she had declared in November 1977. This refreshing directness was a very large part of her appeal.

Yes, of course, the policies were a vast improvement on the dismal mix of corporatism and stagflation that had gone before. Credit must go to Keith Joseph and Alfred Sherman, whose Centre for Policy Studies laid so much of the intellectual groundwork for Thatcherism as an actionable program, as well as to the “dry” (as opposed to unreliable “wet”) ministers in her Cabinet who saw the reforms through.

The scrapping of price, wage and exchange controls; the pursuit of monetary targets to counter inflation; the privatization of firms that had been nationalized by Labour; the sale of council houses; the cuts in income tax rates; above all, the showdown with the unions that culminated in the miners’ strike of 1984-5 — all these were bold changes that had to be implemented in the face of fierce, sometimes violent, opposition.

But what made Thatcherism so impressive to a young punk like me was Thatcher’s own aggressiveness. Yes, there was a streak of punk in her, too — in the way she gloried in confrontation, right to the very end of her 11 years in power. As early as 1975 she had come up with a wonderful line about the Labour Party: “They’ve got the usual Socialist disease — they’ve run out of other people’s money.”

This she contrasted memorably with what she called “the British inheritance”: “A man’s right to work as he will, to spend what he earns, to own property, to have the state as servant and not as master… They are the essence of a free economy. And on that freedom all our other freedoms depend.” It was Hayek armed with a swinging handbag, and I loved it.

Once in power, defiance was her forte. “There really is no alternative,” she declared in June 1980, a line that was soon shortened to the acronym TINA. “To those waiting with bated breath for that favorite media catchphrase, the U-turn, I have only one thing to say,” she told the Tory Party Conference in October 1980: “You turn if you want to. The lady’s not for turning.”

Like a true punk, Thatcher loved a fight. “Oh, but you know,” she said in a 1984 TV interview, “you do not achieve anything without trouble, ever.” And she could put the boot in to lethal effect. “The trouble with you John,” she told a wavering back-bencher in her last, desperate days in office, “is that your spine does not reach your brain.”

That was a condition from which a great many Britons suffered in the late 1970s. But not Margaret Thatcher. “I can’t bear Britain in decline,” she told a BBC interviewer in April 1979. “I just can’t.” And nor could we. She really was the savior of her country. And this old punk will be forever grateful.

In the decades since the golden, gritty age of punk, Soho has been gentrified, bringing a certain respectability to former punk haunts.

The 100 Club black painted basement on Oxford Street survives, but others like the old Marquee Club, where the Stones, David Bowie, Eddie and the Hot Rods, Billy Idol, Generation X and others performed and where the Pistols premiered God Save the Queen, has morphed into the Soho Lofts and a restaurant/bar/music club named for its address: 100 Wardour St.

Leicester Square Theatre was a punk venue called the Notre Dame Hall. The Roxy in Neill Street has become a Speedo shop. St Martin’s School of Art, Charing Cross Road where the Pistols played their first gig is now a Clark’s shoe store.

When not being chased, many punks hung out at Louise’s Club, 61 Poland St. It was a lesbian after-hours bar run by an elderly French woman who dressed in men’s clothing and didn’t discriminate against punkers. The building now operates as the Milk & Honey members bar.

So 40 years ago?

Try 44 years ago.

The Jam formed in Woking, Surrey, England, in 1972 by Paul Weller on guitar and lead vocals together with various friends at Sheerwater Secondary School.

The Third World had no idea. London Punk grenaded Afro-disco shite. It reinvigorated Briton youth identity as a lead cultural movement challenging establishment rules and their elitist imposed globalisation.

Richard Hell is known as the first to spike is hair, the first to rip his clothes, and was generally a leading figure in the origination of punk music and fashion. So much so in fact, that Malcolm McLaren centred Hell as a main influence in the radical aesthetic he took back to Britain with him, and later integrated into his shop ‘SEX’.

This sculpted the future of punk fashion, and McLaren has occasionally been dubbed the ‘architect of punk ideology’. He later went on to form a band, utilising the useless and angry kids that hung out at his shop, and called them The Sex Pistols, and these would wear the clothes his wife designed.

Fashion popularised by The Sex Pistols was seen as a reaction against, as well as a culmination of, a long line of post-war British subcultures (Mods, skinheads, rastas, rudies)’… gaining large levels of media attention and notoriety – by either vomiting in public at Heathrow, or writing songs so controversial that the media would refuse to have them aired.

The ‘Pistols’ inspired tens of thousands of Ordinary British youth disaffected by Tory elitist mass sackings and mass immigration of Niggers to follow in their footsteps.

London Punk rejected and gave the friggen bird to the immigrant wave of Nigger evangelistic Motown and Disco dance crud from black Africa but also the dope Nigger cult Reggae dance cult from Britain’s old slave colony, Jamaica.

London Punk rejected and gave the friggen bird to the immigrant wave of Nigger evangelistic Motown and Disco dance crud from black Africa but also the dope Nigger cult Reggae dance cult from Britain’s old slave colony, Jamaica.

London was calling in the lads to restore and defend London from the poncy black cultural invading menace.

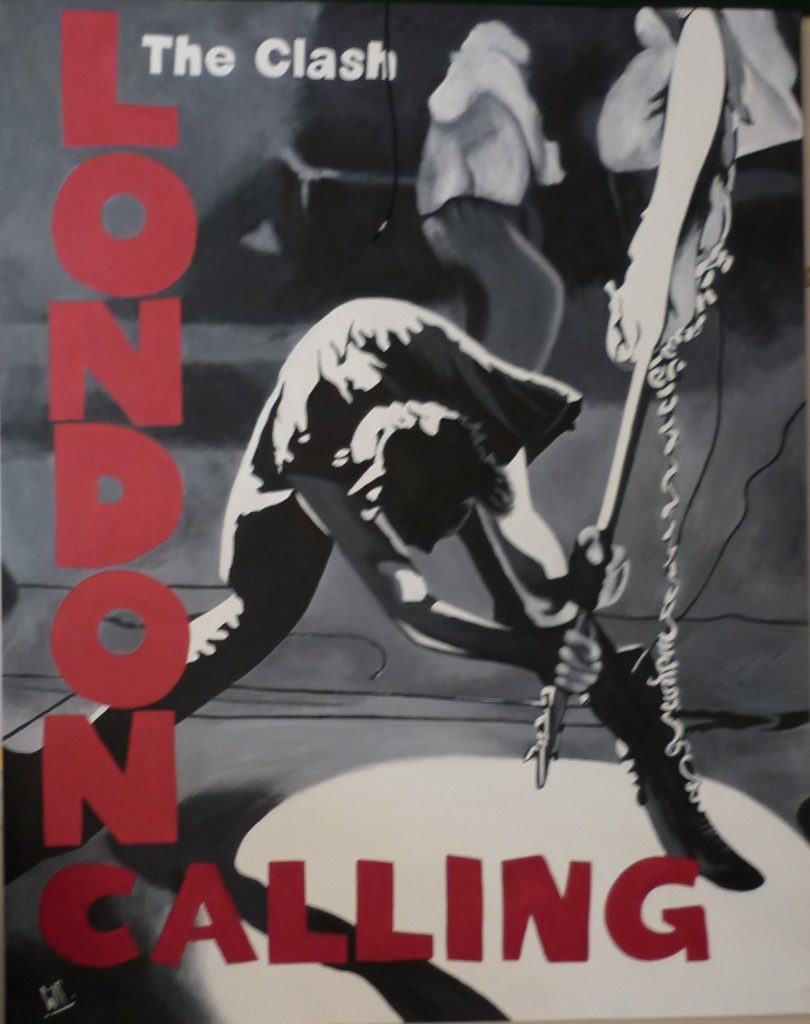

‘The Bromley Contingent’ was the name of just one group of outrageous punks, fans of The Sex Pistols, (and obviously based around Bromley) who would then, within the space of one year, go on to form some of the most influential punk bands to exist; The Clash, Siousxsie & The Banshees, X-Ray Spex, The Slits, and Generation X (young Billy Idol), among others.

‘The Bromley Contingent’ was the name of just one group of outrageous punks, fans of The Sex Pistols, (and obviously based around Bromley) who would then, within the space of one year, go on to form some of the most influential punk bands to exist; The Clash, Siousxsie & The Banshees, X-Ray Spex, The Slits, and Generation X (young Billy Idol), among others.

The Sex Pistols were London’s working class antagonists.

For a decade, proud angry young White Brits kept the black invasion in check.