Independent Ulster, an introduction

Distinctly Ulster:

Ulster in the north is the fourth province on the island of Ireland. Its name derives from the Irish language Cúige Uladh, meaning “fifth of the Ulaidh”, named for the ancient inhabitants of the region.

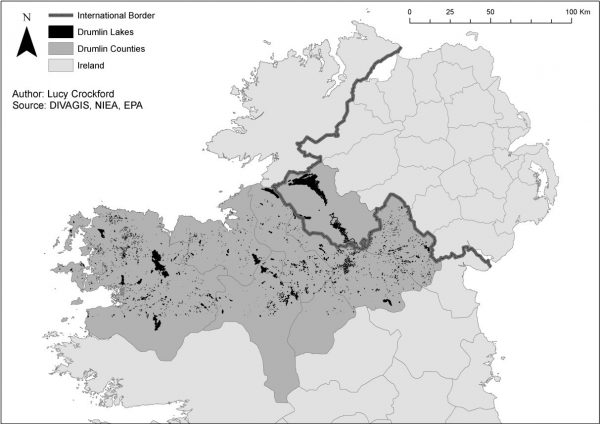

Anthropological evidence shows that the region was settled by Celts during the Palaeolithic era across the seas from nearby Scotland, distinctly from those who settled the south of the island. Ulster is geographically partitioned by ‘the Drumlin Belt‘ – thousands of tightly-packed hillocks, called Drumlins, in a wide belt extending from county Down to Donegal Bay.

Chieftains of the Celtic O’Neill (Niáll) clan reigned over large parts of Ireland until London-centric imperialist English began to invade in the early 1600s.

The bloody left hand of the O’Neill clan predates the Norman Invasion and is recorded on the battle standards of the uá Niáll clan as early as the 5th century.

The flag is based on the crest of the O’Neill Chieftains of Ulster, who were renowned for their strong resistance to English rule, hence the flag is regarded as being Nationalist. Indeed, today many consider those of the name O’Neill the rightful heirs to the title The High King of Ireland.

Since the Norman invasions and conquest, the island was shired and boundaries have been fluid. By the end of the 14th Century, Ulster was the only Irish province completely outside of English control. Rebellions occurred during the 1500s by the local FitzGeralds of Kildare and Desmond with the support of allied clans. But crucially, defeat of the Irish forces in the Nine Years War (1594–1603) at the battle of Kinsale (1601), saw Elizabeth I’s English forces succeeded in subjugating Ulster and all of Ireland.

In 1607 the Irish ruling earls fled from Donegal to mainland Europe, abandoning their people to the will of subordination from London rule.

Westminster-ordered colonisation ensued under the ‘Plantation of Ulster‘ policy by which wealthy landowners from England and Scotland forcibly acquired land holdings and subjugated the locals into serfdom and became Anglicised.

Westminster-ordered colonisation ensued under the ‘Plantation of Ulster‘ policy by which wealthy landowners from England and Scotland forcibly acquired land holdings and subjugated the locals into serfdom and became Anglicised.

Local rebellion against British occupation has been waged by successive Irish generations from 1641 ever since.

Tragically, Westminster trade embargoes on Irish wool on top of prolonged drought drove the population into destitution and forced 200,000 (around half of all Ulster) to flee to the hope of the new world in colonial America from 1717 to 1775. It was called The Great Migration.

Tragically, Westminster trade embargoes on Irish wool on top of prolonged drought drove the population into destitution and forced 200,000 (around half of all Ulster) to flee to the hope of the new world in colonial America from 1717 to 1775. It was called The Great Migration.

In 1920, Westminster’s ‘Government of Ireland Act‘ divided the island into two territories, Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland (Ulster). The area of Northern Ireland was seen as the maximum area within which Ulster Protestants/unionists could be expected to have a safe majority, despite counties Fermanagh and Tyrone having slight Roman Catholic/Irish nationalist majorities.

Ulster nationalism perhaps has its modern origins in 1946 when W. F. McCoy , a former cabinet minister in the Government of Northern Ireland, advocated this option.

He wanted Northern Ireland to become a dominion with a political system similar to Canada, New Zealand, Australia and the then Union of South Africa, or the Irish Free State prior to 1937.

McCoy, a lifelong member of the Ulster Unionist Party, felt that the uncertain constitutional status of Northern Ireland made the Union vulnerable and so saw his own form of limited Ulster nationalism as a way to safeguard Northern Ireland’s relationship with the United Kingdom.

Ulster Nationalism remains a potent school of thought in Northern Irish politics that seeks the independence of Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom without becoming part of the Republic of Ireland, thereby becoming an independent sovereign state separate from both the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland.

British Ulster Dominion Party

The British Ulster Dominion Party (BUDP) was a small group originally formed in 1975 which argued that Northern Ireland should become a self-governing dominion.

Under this particular plan the Queen would remain as monarch and there would be a resident governor-general.

The party began in 1975 as the Ulster Dominion Group, when Professor Kennedy Lindsay broke from the United Ulster Unionist movement (which would later emerge as the United Ulster Unionist Party), itself a breakaway from the Vanguard Progressive Unionist Party to form a new group that would fully support the idea of Dominion status for Northern Ireland.

The UDG wanted effective independence for the Province, although the British monarch would continue as Head of state and would be represented by a Governor-General.

The UDG changed its name to the British Ulster Dominion Party in 1977 when it decided to take a more formalised role in Northern Irish politics. The party put up 4 candidates in Antrim town, Larne Town and Ballyclare in the local elections of that same year but found that it had very little support with none of the candidates being able to achieve even 5% of the vote.

Lindsay himself polled poorly in Ballyclare, finishing last with just 4% of the vote. Thereafter it was obvious that it could not mount a serious challenge to mainstream Unionism, despite the relatively high circulation of its tabloid newspaper The Ulsterman.

Demoralised by the failure of 1977, the party had a very low profile thereafter. In Autumn 1982, shortly before the Assembly elections of October 1982, the party merged with the United Ulster Unionist Party (most of whose members had been former colleagues of Lindsay in Vanguard.) Lindsay stood unsuccessfully as a UUUP candidate in those elections in South Antrim and the UUUP was disbanded 2 years later.

Independence has been supported by the ‘Ulster Third Way‘ (U3W) which followed an Ulster nationalist ideology committed to securing independence for Northern Ireland from both the United Kingdom and Ireland.

The Ulster Third Way was the Northern Ireland branch of the Third Way and was organised by David Kerr, who had previously campaigned as an ‘independent Unionist’ (chairing the small North Belfast Independent Unionist Association) as well as for the British National Front.

As well as sharing the Third Way’s aims U3W (as it is sometimes shortened to) was U3W tended to focus its attentions on trying to build up grass-roots support in loyalist areas, emphasising Ulster-Scots and the 1690 Battle of the Boyne commemorations and has its main office in the Shankill area of Belfast.

The group published a journal Ulster Nation, as well as irregular books and pamphlets about Ulster nationalism. The group compared its aims with those of Neo-Confederate in the Southern United States and declared its support for the re-establishment of the Confederate States of America.

As leader of the group Kerr was a candidate in the 1994 European election for the single Northern Ireland constituency under the title “Independent Ulster”, capturing 578 votes (0.1%) to finish 14th out of 17 candidates.

Kerr also served as a candidate for the larger Ulster Independence Movement.

The party largely confined its activities to the Belfast West constituency, campaigning only there in the 2001 general election (with Kerr winning 116 votes for a 0.3% share).

As well as in the west of Belfast U3W also offered candidates in north Belfast in the 2001 local elections.

The party deregistered on 8 December 2005.

Although the term ‘Ulster‘ refers strictly to one of the four traditional Provinces of Ireland, the name is used to refer to Northern Ireland within unionism and Ulster loyalism, from which Ulster nationalism originated.

Ulster Nationalism has its origins in 1946 when W. F. McCoy, a former cabinet minister in the Government of Northern Ireland, advocated this option. He wanted Northern Ireland to become the Dominion of Ulster with a political system similar to Canada, New Zealand, Australia or the then Union of South Africa—or indeed the Irish Free State prior to 1937.

McCoy, a lifelong member of the Ulster Unionist Party, felt that the uncertain constitutional status of Northern Ireland made the Union vulnerable and so saw his own form of limited Ulster nationalism as a way to safeguard Northern Ireland’s relationship with the United Kingdom.

Some members of the Ulster Vanguard movement, led by William Craig, in the early 1970s published similar arguments, most notably Professor Kennedy Lindsay. In the early 1970s, in the face of the end of Stormont, Craig, Lindsay and others argued in favour of a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) from Britain similar to that declared in Rhodesia a few years previously. Professor Lindsay later founded the British Ulster Dominion Party to this end but it faded into obscurity around 1979.

Loyalism and Ulster Nationalism

Whilst early versions of Ulster nationalism had been designed to safeguard the status of Northern Ireland, the move saw something of a rebirth in the 1970s, particularly following the 1972 suspension of the Parliament of Northern Ireland and the resulting political uncertainty in the province. Glenn Barr, a Vanguard Assemblyman and a UDA leader, described himself in 1973 as ‘an Ulster nationalist’. The successful Ulster Workers Council Strike in 1974, (which was directed by Barr), was later described by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Merlyn Rees as an ‘outbreak of Ulster nationalism’.

After the strike loyalism began to embrace Ulster nationalist ideas, with the UDA in particular advocating this position.[2] Firm proposals for an independent Ulster were produced in 1976 by the Ulster Loyalist Central Co-ordinating Committee and in 1977 by the UDA’s New Ulster Political Research Group.

The NUPRG document, Beyond the Religious Divide has been recently republished with a new introduction. John McMichael, as candidate for the UDA-linked Ulster Loyalist Democratic Party, campaigned for the 1982 South Belfast by-election on the basis of negotiations towards independence.

However McMichael’s poor showing of 576 saw the plans largely abandoned by the UDA soon after, although the policy was still considered by the Ulster Democratic Party under Ray Smallwoods. A short-lived Ulster Independence Party also operated, although the assassination of its leader John McKeague in 1982 saw it largely disappear.

The National Front

While Ulster nationalism went into something of a decline following the South Belfast by-election in loyalist circles, the issue became a matter of policy for the Official National Front, as the Political Soldier wing of the British National Front was known.

During the 1980s the group produced a document entitled Alternative Ulster – Facing Up to the Future which laid out plans for how independence could be achieved and how the independent state would function. Arguing that Ulster represented a nation distinct from Ireland and Britain, they called for an independent state to be run by a series of Community Councils, with an economy based on distributism.

Despite the plans, the NF never had more than minor support in the province and the plans failed to reach a wider audience.

Post-Anglo-Irish Agreement

The idea enjoyed something of a renaissance in the aftermath of the Anglo-Irish Agreement, with the Ulster Clubs amongst those to consider the notion.

After a series of public meetings leading Ulster Clubs member Rev Hugh Ross set up the Ulster Independence Committee in 1988, which soon re-emerged as the Ulster Independence Movement.

After a reasonable showing in the Upper Bann by-election, 1990, the group stepped up its campaigning in the aftermath of the Downing Street Declaration and enjoyed a period of increased support immediately after the Belfast Agreement (also absorbing the Ulster Movement for Self-Determination, which desired a historical Ulster as the basis for independence, along the way).

No tangible electoral success was gained however, and the group was further damaged by allegations against Ross in a Channel 4 documentary on collusion, The Committee, leading to the group reconstituting as a ginger group in 2000.

With the UIM now defunct, Ulster nationalism is represented by the Ulster Third Way, which is involved in the publication of the Ulster Nation, a journal of radical Ulster nationalism.

Ulster Third Way, which registered as a political party in February 2001, is the Northern Ireland branch of the UK-wide Third Way, albeit with much stronger emphasis on the Northern Ireland question. Ulster Third Way contested the West Belfast parliamentary seat in the 2001 general election, although candidate and party leader David Kerr failed to attract much support.

Relationship to Unionism and Loyalism

Ulster nationalism represents a reaction from within Unionism and Loyalism to the uncertain position afforded to the Union by the British government.

Its leadership and members have largely all come from within Unionism and have tended to react to what they viewed as crises surrounding the status of Northern Ireland as a part of the United Kingdom, such as the moves towards power sharing in the 1970s or the Belfast Agreement of 1998 which briefly saw the UIM become a minor force.

In such instances it has been considered preferable by the supporters of this ideological movement to remove the British dimension either partially (Dominion status) or fully (independence) in order to avoid all-Ireland rule.

However whilst support for Ulster nationalism has tended to be reactive to political change, the theory also underlines the importance of Ulster cultural nationalism and the separate identity of the people of Ulster.

As such Ulster nationalist movements have been at the forefront of supporting the Orange Order and upholding the 12th July marches as important parts of this cultural heritage, as well as encouraging the growth of the Ulster Scots language.

Outside the Unionist movement, a non-sectarian independent Northern Ireland has sometimes been advocated as a solution to the conflict. Two notable examples of this are the Scottish Marxist Tom Nairn and the Irish nationalist Liam de Paor.

This is but a snippet into the rich complex history of a people on the periphery of the British Isles and an introduction to their ongoing cultural struggle.

Become wise by being well-read in history.

Sculpture at Rathmullan in remembrance to 1607 when Ireland’s leaders abandoned their people to the invading foe.