Mexico’s former president is ‘not going to pay’ for Donald Trump’s ‘fucking wall’

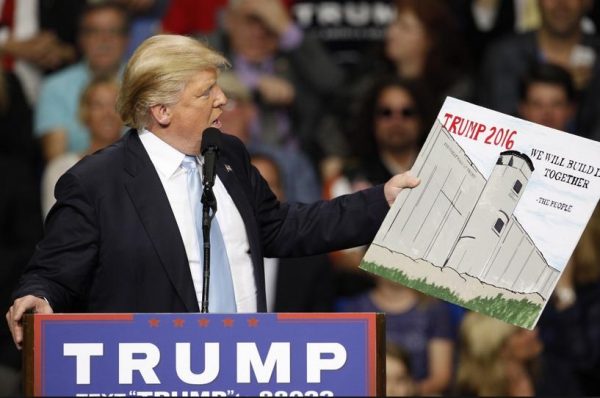

Trump has proposed building an “impenetrable physical wall” on the southern border that Mexico would pay for, beginning on the first day of his administration.

“I will build a great wall — and nobody builds walls better than me, believe me –and I’ll build them very inexpensively. I will build a great, great wall on our southern border, and I will make Mexico pay for that wall. Mark my words.”

– Donald Trump’s electoral pledge to Americans, June 2015.

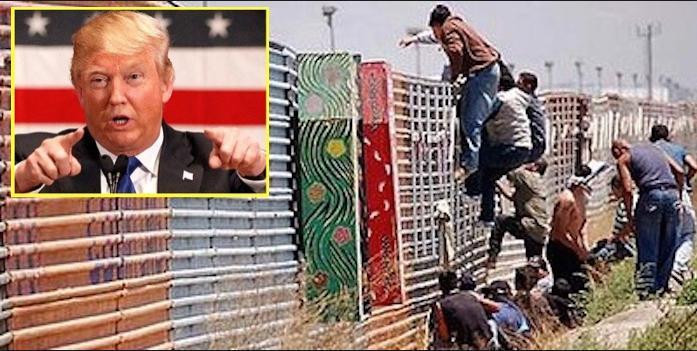

“When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best…They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”

– Donald Trump, June 2016.

The US-Mexican border is 1989 miles long‚ running from California in the west to Arizona, New Mexico and to Texas in the east. It is frequently crossed illegally by not just Mexicans but illegals from south American states and beyond.

Here‚ in his own words‚ are some of Trump’s plans to tackle the US’s migration issues:

“I am going to create a new special deportation task force‚ focused on identifying and quickly removing the most dangerous criminal and illegal immigrants in America who have evaded justice.”

“We’re going to suspend the issuance of visas to any place where adequate screening cannot occur … countries from which immigration will be suspended would include places like Syria and Libya.”

“We will break the cycle of amnesty and illegal immigration. There will be no amnesty.”

Trump has estimated his border wall will cost $12 billion, be constructed of reinforced concrete be up to 55 feet high.

Texas didn’t change with Donald Trump on the ballot. But the differences could be dramatic with him in the White House.

Building the wall will be one of his first tests of electoral credibility.

A wall stretching along the entire 1989-mile border with Mexico is the aim. But a border wall of varying types of fencing exists. Customs and Border Protection between 2006 and 2009 spent $2.4 billion completing 670 miles of a border fence.

Yet in many sections along the US-Mexican national border fencing materials range from three-wire cattle fence, railroad rail, concrete filled thin wall with six-inch steel tube of staggered height, corrugated steel plates, square tubing, or even crushed cars. In some border areas there is nothing. It is a shambles.

All is possible after the billionaire easily won Texas and then the presidency early Wednesday, stunning Democrat Hillary Clinton and the world. What’s next could be an agenda that carries high stakes for Texas’ sizeable immigrant population and relationship with Mexico, and a Trump administration where Texas Republicans old and new could find powerful jobs.

Trump didn’t clinch as dominant a Texas victory as past Republican nominees: His lead was nine points as Texas shattered turnout records with more than 8.2 million voters. Although still a landslide for Trump, his victory stands as the state’s closest presidential race in 20 years.

But Texas Democrats are unlikely to find silver linings in the final tallies. Some of their top political adversaries — Republican Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller — are longtime Trump surrogates who are now poised to feel more empowered in a state already liberally salted with their conservative politics and worldview.

Just days before the election, Miller’s Twitter account called Clinton a vulgar obscenity, which the professional calf-roper deleted and said was mistakenly retweeted.

Patrick said Texas will now have a “good friend” in the White House and hinted that Texas’ constant barrage of lawsuits against the federal government could finally cease.

“This is a great night for our country and a great night for Texas. It is a new day in America,” Patrick said in a statement. “The voices of voters who have been ignored by the Washington establishment, the Democrat establishment and the media establishment, finally were heard loud and clear.”

Republican Gov. Greg Abbott, who didn’t campaign for Trump and conspicuously avoided saying his name at GOP rallies before Election Day, spent the historic night at home in his Austin mansion. He congratulated Trump and said it was “abundantly clear” that millions of Americans felt ignored by Washington.

U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz reluctantly embraced his party’s nominee after failing to beat Trump in the primary, and exit polls suggested that his popularity may have paid a price because of it.

Trump’s victory — and Patrick’s winning all-in bet on the businessman — carried the promise of an even farther rightward GOP that its former standard-bearers likely couldn’t have imagined even a decade ago. In Dallas, a spokesman for former President George W. Bush and wife Laura said they declined to vote for either Trump or Clinton — a rare and remarkable instance of a former president rejecting his party’s presidential nominee.

Trump promised during his bombastic campaign to build a wall across the entirety of the U.S.-Mexico border, called Mexican immigrants “rapists,” vowed mass deportations and provoked tensions with Mexico over trade as well as immigration.

His toughest crackdowns don’t sit well with the majority of Texas voters, according to results from exit polling conducted for The Associated Press. They were divided about the wall — although Trump supporters backed the idea by a 3-1 margin — and more than 7 in 10 voters believe that immigrants working in the country illegally should be given the chance to apply for legal status and not be deported.

Tony Olivo, a 49-year-old driver for a printing company in Dallas, was born in America to parents who both legally immigrated to America from the Dominican Republic. He voted for Trump and said he wasn’t been offended by Trump’s comments about Hispanics.

Tony Olivo, a 49-year-old driver for a printing company in Dallas, was born in America to parents who both legally immigrated to America from the Dominican Republic. He voted for Trump and said he wasn’t been offended by Trump’s comments about Hispanics.

“A lot of people come to this country and they do it the right way. They pay a lot of money. They wait a lot of years, like my Dad did, had to wait a couple of years for him to bring my mom here,” Olivo said.

Hispanics went for Clinton 2-1 but didn’t back her any more than they did Barack Obama in 2008. That’s a likely discouraging sign for beleaguered Texas Democrats, who have banked on a booming Hispanic population to end two winless decades in statewide races. Trump’s win means the state hasn’t supported a Democrat for president since Jimmy Carter 40 years ago.

Remember the Alamo

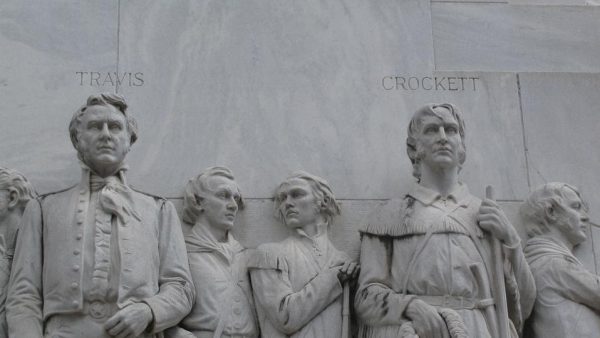

“One of the most gallant stands of courage and undying self-sacrifice which have come down through the pages of history is the defense of the Alamo, which is one of the priceless heritages of Texans. It was the battle-cry of “Remember the Alamo” that later spurred on the forces of Sam Houston at San Jacinto. Anyone who has ever heard of the brave fight of Colonel Travis and his men is sure to “Remember the Alamo.”

Besieged by Santa Anna, who had reached Bexar on February 23, 1836, Colonel William Barret Travis, with his force of 182, refused to surrender but elected to fight and die, which was almost certain, for what they thought was right. The position of these men was known but no aid reached them. The request to Colonel James W. Fannin for assistance had gone unheeded. No relief was in store. As the Battle of the Alamo was in progress, a part of the Texas Army had assembled in Gonzales under the command of Mosely Baker in the latter part of February. From this army, a gallant band of 32 courageous men under the command of George C. Kimble left to join the garrison at the Alamo. Making their way through the enemy lines, these 32 men joined the doomed defenders and perished with them.

On March 2, 1836, during the siege of the Alamo, Texas independence was declared. Four days later, the document was signed with the blood shed at the Alamo. It was under such conditions that Travis and his men fought off the much larger force under Santa Anna. It was with the love of liberty in his voice and the courage of the faithful and brave that Travis gave his men the none too cheerful choice of the manner in which they wished to die.

Realizing that no help could be expected from the outside and that Santa Anna would soon take the Alamo, Travis addressed his men, told them that they were fated to die for the cause of liberty and the freedom of Texas. Their only choice was in which way they would make the sacrifice. He outlined three procedures to them: first, rush the enemy, killing a few but being slaughtered themselves in the hand-to-hand fight by the overpowering Mexican force; second, to surrender, which would eventually result in their massacre by the Mexicans, or, third, to remain in the Alamo and defend it until the last man, thus giving the Texas army more time to form and likewise taking a greater toll among the Mexicans.

The third choice was the one taken by the men. Their fate was death and they faced it bravely, asking no quarter and giving none. The siege of the Alamo ended on the dawn of March 6, when its gallant defenders were put to the sword. But it was not an idle sacrifice that men like Travis and Davy Crockett and James Bowie made at the Alamo. It was a sacrifice on the altar of liberty.

Fannin And His Men

One of the most debated maneuvers of the fight for independence was the Matamoros expedition under the command of Colonel James W. Fannin. Its results were almost disastrous to the cause of the Texans. Its shed of human blood and sacrifice of brave men were even greater than at the Alamo.

The command was engaged in many small skirmishes by a division of Santa Anna’s army under the command of General Urrea. It was in these small skirmishes that the great majority of this command was killed or wounded. One historian labeled this phase of the war the “useless but heroic sacrifice of Refugio, Victoria, and Goliad.”

The fateful blow that wiped out Fannin’s command was struck at Goliad. Fannin and his men were retreating to Victoria from Goliad, when General Urrea with one division of Santa Anna’s army attacked them on March 19. A fierce engagement followed. The attack was renewed on the morning of March 20, when Fannin and his men surrendered as prisoners of war. They were taken back to Goliad. It was one week later, on March 27, when they were massacred.

This small Texas army under Fannin had been brought together from all parts of the American Southwest. Its units, considered in the order of their arrival at Goliad, were:

1. Westover’s Company. (a) A small company of regulars enlisted from among Mexia’s Tampico men, and (b) 14 men enlisted in the Irish colonies.

2. Small volunteer company of 29 enlisted at Bexar.

3. Six companies organized at Bexar (San Antonio Greys, Mobile Greys, United States Independent Cavalry Company, Louisville Volunteers, small artillery company enlisted in New Orleans, company of infantry, including San Augustine and United States volunteers.)

4. The Huntsville Volunteers, from Huntsville, Alabama, and Paducah Volunteers.

5. The Georgia Battalion of four companies–First Company, enlisted at Columbus, Georgia, Fannin’s home town, with men from Alabama and Mississippi; Second Company, Georgia; Third Company, Georgia, with several men from Mississippi and Alabama, and the Alabama Greys.

6. A small company of Kentucky riflemen and a small company of Mexican artillery.

7. Red Rovers, Alabama; 15 men from Tennessee and Mississippi, Company of Refugio Militia, Matagorda Volunteers and approximately 10 additional men.

From the component parts of the army, it can be seen that the Texas fight for independence was not fought by the regular army, that the men who bore arms and gave their lives for Texas independence were volunteers, men who were ready, just as the members of the Texas National Guard today are ready to fight for what they think right. It was at the Alamo, at Goliad, at San Jacinto, that the spirit of the present Texas National Guard was born.

Following the massacres at the Alamo and at Goliad, following the defeats of the Texan army in small skirmishes, when dark clouds hovered over the Texan’s fight for independence, Sam Houston, “man of conquest,” fighter for liberty and justice, took active command of the Texans. His tactics were disputed and severely criticized by many. A later historian, though, declared:

“His principle was sound in the highest degree–to lure the enemy to the banks of the Sabine, far from the base of supplies and source of recruits, and give him battle on a broader land where the Texans could confidently expect military aid from the United States.”

San Jacinto

The retreat of Houston and his army and the trailing of the Texans by Santa Anna set the stage for one of the outstanding battles in the New World. Although many may criticize Houston’s tactics, his retreat, there is none who can doubt the glorious results of his victory at San Jacinto.

When Houston had maneuvered the enemy as well as his own army into the positions he desired, he halted his retreat and attacked. The first shot of San Jacinto was fired about 10 a.m. on April 20, 1836. This was only a skirmish but Houston was satisfied with the results. The fate of Texas hung in the balance and the weight of justice was on the side of Texas.

It was on April 21, that the Texans in solid phalanx, rallying to the cry “Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!” and determined to emerge victorious, rushed forward with relentless fury upon the breastworks of the Mexicans. At the head of the center column rode General Houston.

The Mexican army was drawn up in perfect order, but the Texans rushed on without firing. As they approached the breastworks, the Mexicans greeted them with a stream of bullets, which however, went over their heads. Houston was badly wounded, but the Texans rushed forward. Each man reserved his fire until he could choose his target, then before the Mexicans could reload, the Texans discharged their rifles into their very breasts. Without bayonets, the Texans converted their rifles into war clubs. A desperate hand-to-hand struggle all along the breastworks took place.

When the Texans had, by smashing in the skulls of the Mexicans, broken off their rifles at the breech, they flung the remains at the enemy, and drawing their pistols, continued the slaughter. When their pistols were emptied they drew their bowie knives and carved their way to victory.

The little band of heroes had conquered an army superior in training and equipment and twice as large. Only three Texans lost their lives, 34 were wounded, six mortally. The Mexicans killed totaled 630. The force with which the Texans charged was best described by Santa Anna, himself, following his capture the next day, when he declared:

“So sudden and fierce was the enemy’s charge that the earth seemed to move and tremble.”

It was on the battlefield at San Jacinto that occurred the final chapter in the Texas fight for independence, a glorious chapter that ranks in historical significance with the consultation at San Felipe in 1835 and the signing of the Declaration of Independence on March 2, 1836.

Heroes Of San Jacinto

As in all other battles of the war, the Texas force was composed of men from various sections of the United States as well as Texas. They were volunteers–average civilians in ordinary life but men willing to don the uniform and shoulder arms when their homes and their independence were threatened.

These men, coming from all parts of the country, were united under one flag–the Lone Star. It may be considered symbolical that the Army of Texas had but one flag, which was made and presented to a volunteer company from Newport, Kentucky, by the ladies of Newport. It was carried by James A. Sylvester, who on the day following the battle of San Jacinto captured General Santa Anna.

Besides the Texans and Major General Sam Houston, who was born in Virginia and was former governor of Tennessee, there were fighting for Texas at the battle of San Jacinto men from Virginia, Tennessee, Louisiana, Kentucky, Alabama and other sections. But in the battle, they were truly Texans, fighting for their adopted homeland and throwing off the yoke of tyranny.

There was also born in the fight for independence one of the most respected and effective forces for law and order ever to be known–the Texas Rangers. It was at the consultation at San Felipe in November, 1835, that authority was given for raising a force of 150 Rangers, to be placed in detachments on the frontier. At once, the company of Captain Coleman was organized and had its several detachments placed at various points on the Trinity, Brazos, Colorado and Little Rivers. Thus was born a force that for a hundred years was to maintain the law and order and justice that had been won in the Texas fight for independence.

The War for Independence produced some of the greatest men of Texas history, with the vast majority of them members of the volunteer militia that succeeded in defeating Santa Anna. Such men as Houston, Austin, Travis, Fannin, Lamar, Crockett and Bowie, just to mention a few, set a high example for all members of the Texas volunteer and National Guard forces to follow.

As Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States, said of General John B. Hood’s famous Texas Brigade, “The troops of other states have their reputation to gain, the sons of the Alamo have theirs to maintain.”

First Years of the Republic

Although the War for Independence was won by the Texans, dangers along the border still existed in the form of marauding bands of Mexicans and white renegades who pillaged the outlying settlements. Attacks from Indians added to the dangers of the frontier. So, after the War of 1836, legislative provisions were made for maintaining mounted companies to defend the frontier against Indians, bandits and to keep down local disturbances.

The first volunteer company of the Republic of Texas, the Milam Guards, ever subjected to the commands of the President, was organized in Houston during 1836 with Joseph Daniels serving as captain. The Milam Guards were later commanded by James F. Reily. On its rolls were the names of Judge Peter W. Gray, General E. B. Nichols, Governor F. R. Lubbock and others to the number of nearly one hundred men.

The 141st Infantry, 36th Division, traced its history back to the days of the Texas Republic. The forebear of this regiment was the old “Washington Guards,” which was organized at old Washington, Texas, on April 7, 1836. The original muster roll of the “Washington Guards” is on file in the archives of the State of Texas. It shows every man’s name and grade and is signed “J. B. Chance, Captain.” This was the only organization of the Texas National Guard which could authentically trace its history back to the days of the Republic.

On December 13, 1838, President Mirabeau B. Lamar of the Republic of Texas, appointed the famed General Albert Sidney Johnston as Secretary of War. General Johnston entered upon his duties as Secretary of War on December 16, 1838, and served until March of 1840. He was also the first Adjutant General of the Republic of Texas, having been appointed by President D. G. Burnet on August 5, 1836, and serving until November 16, 1836.

The Burnet Flag from 1836 to 1839 was the national flag of the Republic of Texas until it was replaced by the currently used “Lone Star Flag”; it was the de jure war flag from then until 1879.

Another indication of the part played by the volunteer militia in the early days of the Republic of Texas was contained in a message sent in March, 1839, from Mirabeau B. Lamar to the Harrisburg Volunteers. He congratulated them on their volunteering for service and told them that they would be ordered to march to the invaded portion of the Republic on the Colorado, to cooperate with their compatriots then in the field. This was during the expulsion of the Cherokees from Texas.

Information relative to all the militia companies and military events of the early days of the Republic is not available in authoritative form since the Adjutant General’s office burned in the winter of 1853-54 and the State Capitol in November, 1881, making it impossible to secure authoritative original documents relating to military events between the years of 1835 and 1881.

Through personal diaries and newspaper accounts, though, several enlightening facts on the organization and the spirit that prompted the organization of one of the early militia companies–the Travis Guards–are available. It is supposed that the Travis Guards unit was typical of the many others that were formed throughout Texas during those days.

The Travis Guards were fully organized in the winter of 1839-40 in Austin for home protection and speedy campaign work against Indians who made frequent incursions into the town about that time. In 1840, they were called to San Antonio to assist in repelling Indian incursions. In the Austin City Gazette (Vol 1, No. 17, Wednesday, March 4, 1840), the editor commented on the organization of the Travis Guards as follows:

“A number of the young men of this city have enrolled themselves as a volunteer military company, and adopted the above title (Travis Guards). They have already framed their constitution and by-laws, and on Friday evening next, will meet for the purpose of electing their officers.

“A company of this kind has long been wanted at this place, and, under the direction of efficient officers, cannot fail of rendering essential service to this section of the country. It cannot otherwise than prove the means of inspiring confidence among our citizens as guaranteeing that, in case the hour of danger should again arrive, there will always be a well-organized and disciplined body, on the spot, as a nucleus round which all may rally for mutual protection and defense.

“It is a duty which we conceive the government owes to itself, and the country generally to bestow its fostering care on this company. Austin is situated on the very verge of our frontier settlements, the whole of the archives of the Republic are deposited here; then, most assuredly, in encouraging the organization of a military band for the defense of this place, would the government, not only be assisting in its own protection, but also that of its citizens.

“We have been requested to remind the members of the ‘Travis Guards’ that Friday evening has been set apart for the election of officers. It is hoped that every man who has enrolled his name will be present on this occasion.”

The informality of the organization of the unit, the willingness of the young men of the town to devote their time to the civic enterprise and the necessity of protection were characteristic of all the first militia units. The members of these volunteer companies, even the Texas Rangers, had to furnish their own equipment although they were not paid.

In the following week’s issue of the paper, the names of the officers elected by the Travis Guards were announced. They were M. H. Nicholson, Captain; M. P. Woodhouse, First Lieutenant; A. W. Luckett, Second Lieutenant; G. D. Bigger, secretary, and J. H. Yerby, treasurer.

The Travis Guards were not long in existence before going into action, as on June 15, under the command of Captain Nicholson, they returned to town after a scout of six days. They reported finding the corpse of a man named Rogers, whom Indians had killed and mutilated. The Indians were pursued but they scattered and were not found.

On July 4, 1840, Independence Day was celebrated at Austin by the Travis Guards with a parade, followed by an “oration” by Thomas G. Forster. Although in the month preceding, an artillery company of 60 men had been organized in Austin under Captain Mulhausen, no mention was made of this company in the account of the Independence Day celebration.

That the Travis Guards, typical of the early militia volunteer companies, truly served their communities and were respected and well-thought of by the citizens may be gleaned from a suggestion written to a newspaper by a citizen who suggested that the Travis Guards should not be called upon to stand guard every night while there was a company of regulars in the vicinity “doing nothing.” (Most of the foregoing facts were taken from “Annals of Travis County and of the City of Austin–From the Very Beginning to 1875” by Frank Brown.)

SOURCE: http://www.texasmilitaryforcesmuseum.org/tnghist3.htm

The Lone Star Flag was introduced to the Congress of the Republic of Texas on December 28, 1838, by Senator William H. Wharton and was adopted on January 25, 1839, as the final national flag of the Republic of Texas. When Texas became the 28th state of the Union on December 29, 1845, the national flag became the state flag. Blue stands for loyalty, white for purity, and red for bravery.

The Lone Star Flag was introduced to the Congress of the Republic of Texas on December 28, 1838, by Senator William H. Wharton and was adopted on January 25, 1839, as the final national flag of the Republic of Texas. When Texas became the 28th state of the Union on December 29, 1845, the national flag became the state flag. Blue stands for loyalty, white for purity, and red for bravery.

Swearing in of US Border Control officers, Texas 2013.

Swearing in of US Border Control officers, Texas 2013.

American President-elect Trump has a fight ahead. Mexico’s former president is ‘not going to pay’ for Donald Trump’s ‘fucking wall’.

Trump is set to have a fight on his hands. It will be worth it. Keep the Fesskins out!

Trump is set to have a fight on his hands. It will be worth it. Keep the Fesskins out!