Ulster’s maturity for independence? ..reflecting on some recent attempts

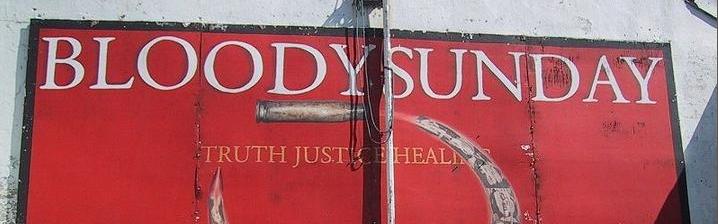

On 30th January 1972 during winter in the poverty stricken and persecuted Bogside area of Derry in Northern Ireland, a peaceful protest had been organised by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association and the Northern Resistance Movement against British military rule and oppression.

British soldiers shot 26 unarmed civilians during a peaceful protest march against internment. Fourteen people died: thirteen were killed outright, while the death of another man four months later was attributed to his injuries. Many of the victims were shot while fleeing from the soldiers and some were shot while trying to help the wounded. Other protesters were injured by rubber bullets or batons, and two were run down by army vehicles.

It was The Bogside Massacre, popularised in the vernacular as ‘Bloody Sunday‘.

The soldiers involved were members of the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment, also known as “1 Para”.

The soldiers involved were members of the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment, also known as “1 Para”.

Two days later the British Embassy in Dublin was burned down and some weeks later the Official IRA killed seven people in a bomb attack at military barracks in Aldershot, England.

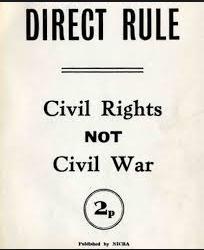

Fearing a full-scale civil war, the British Prime Minister Edward Heath decided Westminster should take complete control over security policy in the province. Northern Ireland Prime Minister Brian Faulkner refused to maintain a government without security powers which the British government. Less than two months later, PM Faulkner and his cabinet resigned in protest He was the sixth and last Prime Minister of Northern Ireland.

The Stormont parliament was subsequently prorogued (initially for a period of one year) and following the appointment of a Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, William Whitelaw, Direct Rule in Ulster by Ulster was introduced.

On that day, the Stormont Parliament met for the last time. Some 100,000 unionists converged to join a two-day protest strike that crippled power, public transport and forced businesses to close. Mr Faulkner was cheered as he walked onto the balcony.

On that day, the Stormont Parliament met for the last time. Some 100,000 unionists converged to join a two-day protest strike that crippled power, public transport and forced businesses to close. Mr Faulkner was cheered as he walked onto the balcony.

Faulkner called for restraint and the unionist crowd dispersed quietly.

Faulkner called for restraint and the unionist crowd dispersed quietly.

But all power now rested in the hands of the new Secretary of State, William Whitelaw. His Northern Ireland Office was responsible for the day-to-day running of the province. Although 1973 would see an attempt at establishing a power-sharing assembly, direct rule was there to stay. So what history has come to know as Bloody Sunday was, in essence, the end of Faulkner’s government.

Direct Rule in Ulster for Ulster as granted from London was initiated in response to increased violence in the province and the apparent unwillingness of the ruling Unionist politicians to accommodate changes at that time.

It brought half a century of unionist control to an end and effectively conceded that Northern Ireland had become ungovernable from Belfast because of the inability of the two communities to work together. But the decision did little to halt the growing violence as paramilitaries on both sides seized the opportunity to fill the vacuum left by the departure of normal politics.

The Stormont ministers had attempted to make some changes, but to the nationalist opposition, they appeared to be too little and too late. It appeared that in the space of three short years, three unionist prime ministers has failed to restore stability and the trust of all sides of the community.

But the catalyst for the imposition of direct rule was the growing friction between London and Belfast over the direction and control of security policy amid worsening violence.

By 1974, a radical proposal by the United Kingdom’s former Prime Minister Harold Wilson envisaged a secret Doomsday Plan to cut all ties between Great Britain and Northern Ireland (Ulster) separate and across the Irish Sea.

It was an idea borne out of London’s failing Home Rule frustration wishing an end to the costly and distracting Troubles at their peak. It was in readiness for a “panic” British withdrawal.

British Prime Minister Harold Wilson visiting soldiers in Londonderry Northern Ireland in 1970

British Prime Minister Harold Wilson visiting soldiers in Londonderry Northern Ireland in 1970

The plan was to allow the 6 counties to become an independent dominion, like Canada, but without Commonwealth membership.

In a memorandum marked “Top Secret”, released to the National Archives on 1st January 2005 under the 30-year rule, Mr Wilson set out emergency proposals for Northern Ireland to be given “Dominion status”, effectively severing it from the United Kingdom.

Under the plan, which was circulated to only his closest advisers, all British funding would have been cut off within five years, although a small army garrison would have been retained. Mr Wilson admitted that the scheme – effectively returning Northern Ireland to Protestant majority rule – would provoke an international outcry and could lead to massive bloodshed.

In documents released in 2005, Harold Wilson informed only his most trusted and senior Cabinet secretaries and advisors of his ambitions to exclude NI from the UK and enable it to become an independent nation, retaining the Queen as head of state but with no political oversight from Westminster. At a time of political crisis, Wilson was desperate to come up with a solution (no matter how radical) to end the conflict in the province.

Wilson’s instructions began:

“All this affects the drafting of any Doomsday scenario. In Doomsday terms – which means withdrawal – I should like this scenario to be considered. It is not the only one by any means and it is open to nearly all the objections set out: … outbreak of violence and bloodshed, possible unacceptability to moderate Catholics, ditto to the Republic, the United Nations and the possible spread of trouble across the water – to name but a few.”

“What I would envisage… when we decided that Doomsday was in sight, we should proceed to prepare a plan for dominion status for Northern Ireland. This would still mean that the Ulstermen were subjects of the Queen.

It would have to be negotiated with all parties and if it were in the next four months, say… It would mean the transfer of sovereignty from Westminister. Dominion status would not, of course, carry guaranteed entry into the Commonwealth. I would think this … most unlikely and so would membership of the United Nations.

“All the UK government functions… in Northern Ireland would be transferred to the new authority. As regards finance, I would imagine the right thing would be tapering off over a period of three to five years.”

However, in the memorandum sent only to his principal private secretary Mr Robert Armstrong, he warned that the worsening situation meant that drastic measures may soon be inevitable. “All this affects the drafting of any Doomsday scenario,” he wrote. “I repeat that this scenario, like any other, leaves more questions unresolved than it answers.

“But it is one possible scenario, and I have a feeling that parliamentary and other pressures may drive us to pretty early consideration of it, or any other alternative.”

Mr Wilson drew up his memo at the end of May 1974 following the collapse of Northern Ireland’s first attempt at power-sharing between unionists and nationalists, agreed the year before at the Sunningdale talks.

He conceded that, in the face of a crippling strike by Protestant workers opposed to the agreement, the British government had effectively lost control of the situation.

“It is clear that we are in the position of `responsibility without power’. The traditional prerogative of something very unpleasant throughout the ages – I think a eunuch,” he reflected gloomily.

The full plan, drawn up for Mr Wilson by officials, is still considered to be so sensitive that it has not been released to the National Archive. However the gist of the scheme is apparent from Mr Wilson’s memo, which made clear that its provisions would almost certainly have to be implemented at very short notice.

The plan appeared to have involved elections to a new constituent assembly, almost certainly ensuring a return to power of the Protestant majority. Mr Wilson said that there would have to be guarantees built in to protect the rights of the minority Catholic population. Even so, he accepted that the plan carried enormous risks.

“It is open to nearly all the objections set out in the document – outbreak of violence and bloodshed, possible unacceptability to moderate Catholics, ditto to the Republic, the United Nations and the possible spread of trouble across the water, to name but a few,” he said.

It could have left Ulster in a state of bloody chaos that could have spilled over to its southern neighbour into a wider ethnic and sectarian civil war. Who knows?

The idea of Northern Irish independence (or Ulster Nationalism) is not one of Harold Wilson’s making. The notion of an independent Stormont Government has it’s roots as early as 1946 when WF McCoy, UUP Member of the Northern Irish Parliament (NI had a ‘functioning’ parliament with 52 MPs, a Senate and a Prime Minister from 1921 to 1972) became concerned that the British Government could easily vote NI out of existence and hand it over to Ireland unless safeguards were put in place.

His proposals were that NI become a Royal Dominion with an independent Government, free from the machinations of a British Government that he did not fully trust.

McCoy’s ideas, as history dictates, we’re rejected by the majority of Unionists and the movement never gained any momentum. It wasn’t until 1972 that the idea would come back to the surface when the Ulster Vanguard movement, led by William Craig, published their booklet ‘Ulster – A Nation’ in April of that year.

The document heavily criticised the imposition of Direct Rule on Northern Ireland whilst also opposing any idea of power sharing or devolution with Republicans and Nationalists.

In September of ’72 the Ulster Vanguard proposed a restoration of the NI Parliament and a Bill of Rights to safeguard minorities whilst also advocating the ‘extermination’ of the IRA.

As time moved on and the political situation changed, these policies faded away and so did the Ulster Vanguard by February of 1978.

It was after this that the links between Ulster Nationalism and Loyalist Paramilitaries became stronger. The 1974 Ulster Worker’s Council strike brought about the collapse of the short lived power sharing executive and Harold Wilson began fishing for other alternatives.

The likely outcome, as Wilson’s own advisors admitted, was an explosion of violence in Northern Ireland that would spill across the border into the Republic of Ireland and even into mainland GB itself. A sectarian war between the Northern Irish state, the IRA and Loyalist paramilitaries was a guaranteed outcome.

Wilson even floated the idea to the SDLP which horrified them. John Hume went so far as to suggest that if Loyalists gained power over an independent NI, they would be able to change the constitution and effectively manufacture an apartheid state between a Protestant ruling majority and a Catholic minority. The idea quickly perished and Wilson’s Government collapsed shortly after.

The documents and proposals were never released to the media until 2005. The Irish Government at the time also opposed the idea as they had concerns that without British military intervention their 12,000 strong defence force would be unable to contain the spread of violence. They believed that any increase in defence or military spending in the Republic would also be seen by Loyalists as aggression who would do likewise, possibly leading to a devastating war between North and South.

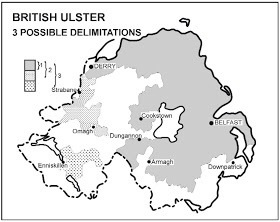

Nearly ten years later in 1986 the The Ulster Movement for Self-Determination was formed. They envisioned an independent Ulster with the 6 counties of Northern Ireland along with the 3 counties of Cavan, Monaghan and Donegal that were in the Republic of Ireland’s jurisdiction.

In 1988, post Anglo-Irish Agreement, the NI secessionists had a revival in the form of the Ulster Clubs’ Ulster Independence Committee which in turn became the Ulster Independence Movement (UIM).

After the 1990 by-election in Upper Bann in which the UIM candidate Hugh Ross gained 1,534 votes (4.3%) they began campaigning earnest to see their vision for an Independent Ulster become a reality and they absorbed the USMD.

However without any major backing by any mainstream Loyalist paramilitary grouping or other financial support from other factions of Unionism the USMD effectively vanished by 1994 and the UIM closed up shop by 2000.

A much more sinister plan for Ulster Nationalism was devised by the UDA in January of 1994 with a document proposing an ‘ethnic Protestant homeland’ in Northern Ireland following a long feared British withdrawal from the province. Their plans consisted of redrawing the border of Northern Ireland to include areas that were majority Protestant and ceding the rest to the Republic of Ireland. A horrific proposal to ‘nullify and expel’ the Catholic population living in the new, smaller and Loyalist dominated Northern Ireland was floated.

No doubt euphemisms for sectarian cleansing throughout the new independent state. The new border that the UDA hoped to draw across Northern Ireland was based on the work of Liam Kennedy, author of the 1986 book Two Ulsters; A Case for Repartition. Although Kennedy was reportedly unhappy about the UDA’s use of his work, more hard line elements within Loyalism were not unhappy with these proposals and the idea of ethnic cleansing was seriously considered.

The idea eventually faded as the map below shows.

Should the Scots eventually vote ‘Yes’ to independence then the idea of a United Kingdom will be challenged at a constitutional level.

It’s possible that the name UK will no longer apply and the new entity of England, Wales and NI would require a new ‘label’. It is then that the conversation may turn to federalism as Wales, Northern Ireland and perhaps even Crown Dependencies such as the Isle of Man and Jersey will begin to ask for greater autonomy over fiscal matters and legislative powers.

At present could an independent Northern Ireland succeed, given Stormont’s fractiousness, dysfunctionality and corruption even with it granted delegation for basic domestic policy issues.

NI has no natural resources, industry or pool of skilled workers or academic assets that could afford us an advantage on a global stage let alone within the British Isles or Europe.

The guts of the memorandum were the Doomsday preparations necessary in the event of a British withdrawal from Northern Ireland. It included a review of how the Irish government might respond in the event of the three worst-case scenarios after a withdrawal:

- An independent Northern Ireland

- Northern Ireland being placed under United Nations trusteeship

- A re-partitioned Northern Ireland.

Three related and lengthy discussion papers from the Interdepartmental Unit on Northern Ireland (IDU) – on the implications of negotiated independence, on the implications of negotiated repartition, and on the possibilities of the Irish government providing military and other assistance to the Northern Ireland minority – were circulated to government with the memorandum.

These submissions had been prepared against the backdrop of continuing deadlock in Northern Ireland.

The failure of Harold Wilson’s Labour government to take effective action against the Ulster Workers’ Council strike and the collapse of the power-sharing executive in May 1974 had created an enduring distrust in Irish government circles and among Northern nationalists of Wilson and of Merlyn Rees, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland.

That distrust had been compounded by rumours – which last year’s release of the 1974 papers showed to have substance – that Wilson’s government was seriously exploring the prospect of withdrawing from Northern Ireland. Fears that the Wilson government was seeking a negotiated withdrawal were exacerbated by the negotiations between British officials and Provisional Sinn Fein that led to the IRA’s ceasefire in February-March 1975.

The elections in May 1975 to the Northern Ireland Constitutional Convention, which the British hoped might produce compromise, instead tightened the political deadlock when the Unionist coalition opposed to power-sharing won an overall majority. The Foreign Affairs memorandum anticipated that the convention would report before the end of the year and, in the likely event of that report proving unacceptable, the British might take apocalyptic decisions within months.

Such apprehensions were reflected in an alarmist story by Conor O’Clery – who had excellent sources in Iveagh House – in the Irish Times on June 4, 1975. Under the headline ‘Withdrawal Gains in British Plans’, it stated that:

“A complete withdrawal from Northern Ireland, or an extension of direct rule for a limited period. From our point of view, Protestant rule, in view of the security methods which it would be likely to employ, is far worse than British rule’ are now believed to be the only alternatives the British Government will consider in the event of the Northern Convention failing to produce a solution acceptable to both communities.”

It was this kind of alarmism that prompted Conor Cruise O’Brien’s vigorous repudiation of the Foreign Affairs memorandum. He particularly objected to the “preparations for a ‘fallout’ position in the event of British withdrawal” and to the assumption that the “least undesirable” development in such an event would be “negotiated independence with maximum guarantees, including a possible United Nations presence in Northern Ireland”.

Cruise O’Brien argued that even the exploration of negotiated independence as a fall-back position “would diminish the prospects of continued direct rule and would tend in effect to let the British ‘off the hook’ by enabling them to withdraw in a favourable international climate”.

He also argued that the loyalists would inevitably be the dominant force in an independent Northern Ireland, that the response of loyalist security forces to any continuation of the IRA campaign would “bear very hard indeed on the minority population”, and that calls for armed intervention by the Irish government could do little to protect the minority.

An ineffective armed intervention “would precipitate even greater disasters” – even, possibly, “a full scale massacre of Catholics” – and the Irish government “would carry inescapably the responsibility for the sequence of events”. The “harsh reality”, concluded Cruise O’Brien, was that:

“The choice lies between British rule and Protestant rule. Protestant rule is what would follow British withdrawal. From our point of view, Protestant rule – in view of the security methods which it would be likely to employ – is far worse than British rule. In these circumstances it is quite clearly in our interest to do everything possible – which may not be very much – to try to ensure that the British stay, and it is certainly not in our interest to take steps which would make it easier for them to go.”

Cruise O’Brien likewise rejected the SDLP’s suggestion of discussions with the Irish government with a view to an exploratory initiative on the preferred fall-back position with the British government.

Dermot Nally, then an assistant secretary in the Taoiseach’s Department and the key figure there in shaping Northern Ireland policy since January 1973, was even more dismissive of the SDLP’s being accorded undue influence over government policy in a memorandum for the Taoiseach on the same day. He also argued that, in the event of the convention coming to nothing, the best prospect was “that the British will continue in Northern Ireland in the hope that a solution may be found in time”, though he, too, was pessimistic about their continuing “direct rule as it is at present – involving London ministers and extreme remoteness of control and administration”.

If the British did pull out, he thought the likeliest outcome not unification but an independent Northern Ireland comprising either the six counties or, more probably, the area east of the Bann. His key sentence was underlined for emphasis:

“The likely prelude to the establishment of a state comprising either the entire six counties or the part of it east of the Bann is so horrific for the entire island that I think we should, on no account, give any support or engage in any open analysis or discussion on the subject.”

This especially included “any analysis or discussion, which have even the semblance of official backing, with the SDLP”. Nally argued that the interests of the Irish State, even, perhaps, of the entire island, “diverge markedly from the interests and policies of the SDLP and a reasonable degree of progress for the three million people living here is more important, no matter what Northern interests think, than power sharing, if the choice comes to that”. Nally accordingly recommended to the Taoiseach “that no option other than options involving the continuance of a British presence in Northern Ireland, with direct rule in some form or other, should be discussed or acknowledged in conversations with the SDLP or others”.

He likewise regarded the likelihood of UN intervention in the event of violence as “extremely remote” and advised that if Foreign Affairs wished to explore the possibility they should do so only”in a very discreet way, involving no disclosure of what they are about”.

Dermot Nally reinforced these arguments in another memorandum to the Taoiseach on July 7 after a discussion with him that morning of three possibilities – a continuation of the British presence, an independent Northern Ireland or a British withdrawal. That Nally here took an even stronger line – arguing that the “advantages” of a continued British presence were “so great, that we should do everything possible to ensure it comes about” – suggests that his earlier pleas had not fallen on deaf ears.

He also thought “it would be well to disillusion the SDLP of any ideas they may have that this country, or any other external force, could or would provide worthwhile guarantees of civil rights etc in an independent Northern Ireland” and, “discreetly, to dispel SDLP illusions as to the capabilities of the Irish Army in any situation of confrontation in Northern Ireland”.

Dispelling SDLP illusions, discreetly or otherwise, was a matter of great delicacy for a coalition government which numbered Conor Cruise O’Brien in its ranks and which was fully aware of the SDLP’s preference for Fianna Fail governments. No such exercise seems to have been attempted in a meeting between ministers (the Tanaiste, Brendan Corish, and Garret FitzGerald) and the SDLP (John Hume and Austin Currie) on August 14, although Garret FitzGerald cannot have been reassured by John Hume’s response to his asking about a fall-back strategy if the unionist coalition rejected power-sharing: “the SDLP had as yet no fixed position on this matter”.

A conversation on August 23 between Garret FitzGerald and James Callaghan, the British Foreign Secretary, after dinner in west Cork where they were both on holiday – that Jack Lynch, then leader of the opposition, was also present testified to the importance attached to preserving a bipartisan Northern policy – seems to have gone some way towards soothing nerves in Dublin; in particular, Callaghan’s assurance that the British government “would not abdicate its responsibilities” but would “take the necessary action to deal with a doomsday situation”.

And Callaghan made further soothing noises at a lunch in Garret FitzGerald’s holiday home in Schull on August 26. Regular telephonic communication between Dermot Nally and Maurice Hayes of the convention secretariat also helped to lower the temperature with the consequence that the last months of 1975 saw little of the freneticism that had characterised the June-July crisis.

Firm conclusions about that crisis on the basis of a few days’ preliminary research in the National Archives and without the time to discuss these documents with any of the surviving participants would be premature. Dermot Nally’s memoranda nevertheless bear the hallmarks of a line drawn firmly in the sand against any further erosion by the SDLP of the Irish State’s vital interests in the shaping of Northern policy.

Although there are no indications of how Liam Cosgrave reacted to the memorandum beyond his initialling it without comment next day, the fact that formal discussion of the Foreign Affairs memorandum was again and again postponed and ultimately withdrawn from the Cabinet agenda, suggests that the arguments advanced by Conor Cruise O’Brien and by Dermot Nally prevailed.

SOURCES:

- ‘Independent Republic of Northern Ireland?’, June 27, 2014 by stevedonnan

- ‘Doomsday’ plan for North revealed in archives, Sat, Jan 1, 2005, Irish Times newspaper

- ‘How Dublin prepared for the threat of NI doomsday’, 1 Jan 2006, by Ronan Fanning (Professor of Modern History at University College Dublin), in Irish News newspaper.