No to THE RACIST VOICE, we’re all Australians Albo

Dysfunctional Alice Springs is a microcosm of what THE RACIST VOICE will inflict on Australians.

Beware voters, THE RACIST VOICE is not some benign symbolic gesture to give minority Black fellas a greater more equal say. It gives them a greater say than non-Black fellas.

It’s privilege according to race. May be worth the vote of say 4 White fellas or 3 brown ethnics? It is most clearly THE RACIST VOICE to override Australian parliamentary democracy by introducing a third star chamber for Blacks only (Aboriginal-only Blacks that is).

It’s dystopian totalitarianism based on race, minority race; South Africa apartheid revisited with no lessons learned.

The RACIST VOICE won’t fix past injustices, Aboriginal poverty, truancy, alcohol-fuelled violence, the safety of women and children, gambling, domestic violence, incarceration, Aboriginal disadvantage, poor life expectancy, high child mortality, remote slums, poor access to education and employment. It won’t improve the quality of life of Aboriginal Australians. It won’t close the gap between Aboriginal people and non-Aboriginal people.

Racial discrimination, institutionalised division, disrespect, intolerance, bigotry, hate, prejudice, segregation, subsidised apartheid, sit down money (subsidised idleness), weaponising racism, perpetuating victimhood, deaths in custody. This is what The Voice will persist and be inculcated.

Who funds THE RACIST VOICE? Where are these Aboriginal Separatists going to get their coup funding to unravel the Australian nation? White wealth to pay for Black sovereignty? Where else will the funding for an Aboriginal-only third chamber come from? The Chinese Communist Party?

Talk about leaping from generous sit down money into into the fire of dictatorship. Ask the indigenous Uyghurs how Chinese Communist Party looks after their interests, not.

No non-Aborigines allowed – NO Whites, Asians, Africans, Pacific Islanders, foreigners, or immigrants. Is this next for THE RACIST VOICE’s secret agenda? The Aboriginal-only third chamber will be a gated community.

THE RACIST VOICES is only phase one of THE ULURU COUP STATEMENT (decree).

This is the very statement that Albo (current Labor PM Anthony Albanese) upon opening his victory speech after Labor won the 2022 election on Sunday 22nd May 2022 confirmed to Australians:

“I begin by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land on which we meet. I pay my respects to their elders past, present and emerging. And on behalf of the Australian Labor Party, I commit to the Uluru Statement from the heart in full.”

This is the ‘ULURU STATEMENT FROM THE HEART’ verbatim:

We, gathered at the 2017 National Constitutional Convention, coming from all points of the southern sky, make this statement from the heart:

“Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and customs. This our ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our culture, from the Creation, according to the common law from ‘time immemorial’, and according to science more than 60,000 years ago.

This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.

How could it be otherwise? That peoples possessed a land for sixty millennia and this sacred link disappears from world history in merely the last two hundred years?

With substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this ancient sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood.

Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people. Our children are aliened from their families at unprecedented rates. This cannot be because we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers. They should be our hope for the future.

These dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. This is the torment of our powerlessness.

We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country. When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country.

We call for the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution.

Makarrata is the culmination of our agenda: the coming together after a struggle. It captures our aspirations for a fair and truthful relationship with the people of Australia and a better future for our children based on justice and self-determination.

We seek a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations and truth-telling about our history.

In 1967 we were counted, in 2017 we seek to be heard. We leave base camp and start our trek across this vast country. We invite you to walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a better future.”

A “better future” for which race only?

A Makarrata Commission is Aboriginal code for reversing Australian sovereignty. It prescribes a treaty and power transition of Australia from Australians to pre-Australia Aborigines. It is Aboriginal separatism, to be enshrined in the Australian Constitution (before it is ultimately renamed to some unpronounceable long Aboriginal word).

It’s akin to how the Maori want to rename New Zealand as Aotearoa. Problen is that often NZ has no white cloud, but is otherwise quite clear skies and sunny, with lots of green pastures and productive sheep.

Beware of this retro-dreamtime wedge attempt to undermine and reverse Australian sovereignty by stealth.

And what about part-Aborigines? Will they be granted just a part of the vote in THE RACIST VOICE? What about if someone’s distant great great uncle’s second cousin twice removed had full blood Aboriginality. So what are the permutations and combinations of that descendant having a percentage say in THE RACIST VOICE?

But THE RACIST VOICE will perpetuate paternalistic policies by Aboriginal elites over Aboriginal non-elites, since some Aborigines included in THE RACIST VOICE will inevitably become more equal than other Aborigines.

Key Wyatt doesn’t look very Aboriginal

THE RACIST VOICE is the wrong way to recognise Aboriginal people or help Aboriginal Australians in need. Race-based measures in the Australian Constitution? How unAustralian, and indeed anti-Australian! This is Aboriginal Separatism!

The Voice to Parliament is a distraction from important issues affecting ordinary Aboriginal Australians.

Aboriginal Australians do not need more voices; they need a way into wider Australian society. There are already Aboriginal voices in the Australian Parliament and at all levels of government through the country we call Australia.

Australia already has a proven political system for including people from all backgrounds. Significantly, there has never been a time in our nation’s history where more people from an Indigenous background have been elected to Parliament. The proposed Voice will only produce division and resentment.

If there is one big brother VOICE holding the only megaphone in the room, what happens to all those other Aboriginal voices? Do they get muzzled as second class voices?

With more than 500 different Aboriginal peoples in Australia speaking more than 150 tribe and language will THE RACIST VOICE adopt?

Beware the rising and dangerous Aboriginal elite class!

This is yet another extreme leftist campaign of treachery hoodwinking naive Aboriginal separatists to try to undermine Australia’s sovereignty. Funded by whom? Ordinary Australian taxpayers.

“My way or the highway!” Early signs of a black Orwellian dystopia, following failed African states.

Contributing to the NO Case:

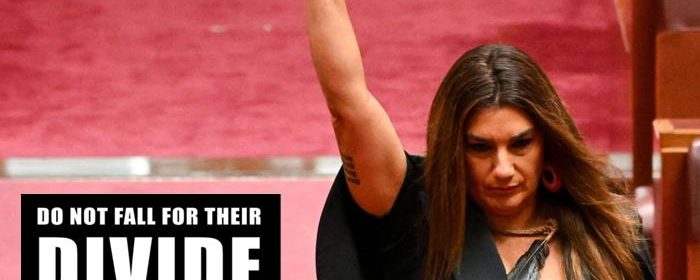

Senator Lidia Thorpe is of part Aboriginal and European descent. She biasely denies her European heritage as if she’s some full blood white Aboriginal.

She politically demands she wants “real power” and “won’t settle for anything less’. She is race-driven and wants “ten independent (unelected) Blak (sic) seats in the parliament today”. If they sit in the House of Representatives, seven per cent of members would be indigenous in perpetuity. A case of one country, two systems.

For Aborigines trapped in town camps and remote communities, whether Prime Minister Albanese or Senator Thorpe prevails matters little. They will remain marginalised.

Nowhere in the world has subsidised apartheid of a minority succeeded. Sadly, too few are willing to accept this reality.

Never forget, it was Aboriginal Adam Giles MP who as Northern Territory’s then Chief Minister, leased Australia’s strategic northern Port of Darwin in October 2015 for 99 years to the Chinese state owned Landbridge Group for A$506 million.

Never forget, it was Aboriginal activist Geoff Clark who chaired PM Bob Hawkes Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) in Darwin (1990-2004) who misappropriated $2 million belonging to the Framlingham Aboriginal Trust over a period of around 30 years.

In the referendum, Australians of all persuasions are being asked to give one racial group – and their descendants for all time – constitutionally guaranteed additional influence over all areas of public policy. If you tick the right race box you would gain political influence exceeding that enjoyed by every other Australian.

THE RACIST VOICE will thus abandon the egalitarian nature of Australian democracy and unravel all the hard work our forebears achieved to avoid civil war.

Never forget how rich Rhodesia became impoverished civil war Zimbabwe

The VOICE: The Case for Voting NO (Chris Merritt, Vice-president of the Rule of Law Institute of Australia and Rule of Law Education Centre, 3 February 2023)

This referendum is not about reconciliation. Nor is it about symbolism and being nice. It is about establishing a new institution of state that would permanently change our system of government. It would require us to abandon equality of citizenship by giving constitutional standing to a race-based entity that could go beyond indigenous affairs and involve itself in all public policy debates.

Without such limits, this looks like an attempt to establish a shadow government that would be free to develop policies on everything. Those policies would be formally framed as advice but, according to prime minister Anthony Albanese, it would be a brave government that ignored its advice.

If the prime minister’s assessment is correct, it would mean the voice would sit uneasily alongside the doctrine of responsible government in which governments are held accountable for their actions first to parliament and then to the people.

In the new world of the voice, the business of government would never be the same.

Governments would inevitably find themselves making trade-offs not just with the opposition and various groupings in the senate, but with members of the national voice and their masters at the regional and local voices that are yet to be established. These local and regional groups would control appointments to the national body and would be the new powerbrokers.

Exactly how voice members will be appointed is just one of the details that has not been resolved. But those who have worked on this proposal have designed an institution that would suffer from a democratic deficit.

And because the voice would be at the heart of our system of government, that malaise would weaken Australian democracy.

The final report of the Indigenous Voice Co-Design Process raises the prospect that some members of the voice may simply be nominated by the local and regional voices while others might be elected. That erosion of democratic principle weakens the case for incorporating such an entity in the Constitution.

But that is not the only departure from democratic principle. One of the most startling proposals in that report is that the distribution of members of the voice between the states should be done in a manner that can only be described as a gerrymander.

According to figures published in September last year by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, NSW has 339,546 Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders which gives that state 34.5 per cent of the nation’s indigenous population of 984,002 – the highest proportion of any state.

Yet the report of the Indigenous Voice Co-Design Process would give NSW a total of just three representatives on the proposed 24-member voice. So the state with 34.5 per cent of the nation’s indigenous people would receive 12.5 per cent of the seats on the voice.

Other states with three seats on the voice would be South Australia which has just 52,083 indigenous people, the Northern Territory (76,736 indigenous people) and Western Australia (120,037). Together, those three states would have nine seats on the voice – or three times the representation of NSW – yet their combined indigenous population is 248,856 which is 90,690 fewer than the indigenous population of NSW.

That report, co-chaired by Tom Calma and Marcia Langton, would amount to a raw deal for indigenous people in NSW and an extremely favourable deal for those in Queensland. It treats the Torres Strait Islands, which are part of Queensland, as a separate jurisdiction and would give them two seats on the voice plus an additional seat for those islanders who reside on the mainland.

When those three seats are included in Queensland’s tally, the sunshine state would have six of the 24 seats on the voice – twice as many as NSW. Yet the ABS population estimates show that Queensland has just 273,224 Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, which is 66,322 fewer than in NSW.

These departures from democratic principle would not be tolerated in any other representative body, state or federal, that is part of this country’s system of governance. Yet this plan for the voice would deprive the nation’s largest cohort of indigenous citizens – those in NSW – of fair treatment.

These shortcomings were not mentioned by the prime minister when he rose in the House of Representatives on November 30 last year holding a copy of the Calma-Langton report, and said: “There are 280 pages of detail about how the voice will operate.”

The proponents of the yes case need to explain why the interests of indigenous people in NSW are considered less important than those of indigenous people in Queensland and other states.

If they have other ideas for the voice, now is the time to disavow Calma-Langton and make the next plan public.

The real issue for the broader community concerns the adverse impact of the voice on day-to-day policy-making. Because the voice would have an unlimited jurisdiction and a narrow race-based constituency, it is entirely foreseeable that government policy on key issues could be skewed away from the broader national interest in order to appease the voice or gain its support.

Constitutionally, governments would still need to maintain the confidence of parliament. But if Albanese is right, political reality would give all governments a strong inventive to placate the voice.

Formally, the voice would merely be providing advice. But in practical terms, it would have real influence over the development of public policy affecting the broader community while remaining accountable only to its race-based constituency.

All groups in society, including indigenous communities, have interests that need to be balanced. Giving constitutional standing and public funding to any single community group would rig the process of balancing conflicting interests and allocating resources, which is the core business of government.

Rejecting such a distortion of the democratic process does not mean closing our minds to the views of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Indigenous people – like everyone else – already have a voice on all matters of public policy through their rights of citizens.

Most people may not be aware of how far the back-room conversation has moved on from symbolic recognition of indigenous Australians. At some point the objective became “substantial” recognition. And the design of the voice went beyond the creation of an advisory group on indigenous affairs to something much more ambitious.

On the table today is a proposal to create a permanent institution of state that would be entitled to develop and prosecute its own policies independently of parliament and the government of the day. It would have everything it needed to establish itself as a shadow administration that, unlike parliament, would not be required to serve the broader national interest, but would instead give priority to its own relatively narrow sectional interests.

The referendum raises a number of questions in relation to:

1) Equality between all Australians

2) The scope and power of the voice

This conversation has become complex and confused, mainly because of the lack of community-wide consultation to date. The blame rests entirely with the government which chose to break with tradition by failing to present official arguments for and against the proposed change, as well as detailed and independent legal analysis.

In past referenda, federal governments fostered debate by providing a pamphlet containing 2000 -word essays giving the official cases for and against the proposed changes. But this time that will not happen and the government even tried to stifle debate by implying that those with concerns are racists.

On November 25 last year, just before the abandonment of the traditional information pamphlet became official, Pat Dodson, the government’s special envoy on reconciliation, told a panel discussion on the voice in Melbourne: “The government is not interested in supporting any racist campaigns, which will have an impact on the question of the pamphlet.”

1. EQUALITY

Do we want to establish a Race-Based Institution of Inherited Privilege?

To gain an insight into the importance of equal treatment, consider this: Last year marked the sixtieth anniversary of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1962 that granted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders the option of voting at federal elections. Mandatory voting at those elections, which followed in 1983, put indigenous people on exactly the same footing as all other Australians.

This took far too long, as did the abolition of the last remnants of the white Australia policy which only took place between 1966 and 1973. Yet those changes show what can be achieved when nations are guided by the doctrine of equal treatment regardless of race.

Equal treatment is fundamental to what it means to be Australian.

It helps explain why, in 1902, the newly established federal government was among the world’s first to enfranchise women voters. South Australia was even earlier, giving women the vote in 1894.

These great reforms all gave effect to the principle of equality. It would be tragic to discard a principle that has served us so well, particularly if this were done as part of some misguided attempt to make amends for the racial intolerance of the past. The damage inflicted by racist policies cannot be denied. But the very source of that damage was the absence of equal treatment. We cannot repeat that mistake.

The referendum that now confronts the nation invites us, once more, to exclude indigenous people from the great principle of equality that was forcefully expressed in the United States Declaration of Independence and which is present in true democracies. Our own history shows that the denial of this principle, regardless of the motivation, leads to catastrophic outcomes.

If this referendum succeeds it would not make up for past injustice. It would do the reverse. It would entrench racial preference, placing this country in the same category as Malaysia, where ethnic Malays enjoy legally sanctioned racial preferences over citizens of Indian and Chinese ethnicity. It would show that we have learned nothing from the racism of the past.

This is the antithesis of the principle espoused by American revolutionaries Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin who considered it self-evident that we are all created equal. Revolutionary France, under Jefferson’s influence, embraced this idea in its Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. It is also present in the first sentence of the first article of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drawn up by the United Nations in 1948 and Australia was one of the original signatories. Article one says: “All human beings are free and equal in dignity and rights . . . “. Article two says: “Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this declaration without distinction of any kind, such as race . . . “.

There is another problem. On January 28, Janet Albrechtsen wrote in The Australian that if the referendum succeeds, it may well amount to a serious breach of Australia’s obligations under the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

If legal advice had been obtained from the Solicitor-General she wrote that it might have found that permanently entrenching racial preferences will make this nation a genuine international pariah.

If the referendum succeeds, everyone would still have the same right to vote and to seek to influence public policy. But those represented by the voice would have something extra.

They would be represented not only by their members of parliament but by a separate lobby group with constitutional standing, public funding and its own bureaucracy.

Those who quibble about whether this would create an extra right for indigenous people have missed the point. The reality, regardless of how it is termed, will be that Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, through their representatives on the voice, would have greater constitutional standing than people of other races.

This would put an end to the idea that all Australians are entitled to an equal say on how this nation is governed. It would entrench racial division and kill reconciliation by fostering resentment against the beneficiaries of such an obviously unfair and unprincipled system.

Australian democracy might not be perfect. But it is the result of a great multicultural project, drawing on the doctrine of equal treatment and the experience of all peoples represented by our federal and state parliaments.

It involves weighing up the needs of all groups taken together and deciding policy that works in the national interest of the whole community.

Putting that collective project first does not make the “no” case racist, or against reconciliation. Every day the peoples of this nation acknowledge Aboriginal presence like never before and celebrate its culture and contributions.

Embracing the voice would mean embracing a system of inherited privilege which has no place in modern democracies.

2. SCOPE

Do we want a Race-Based Institution to propose its own policies affecting the whole community?

One of the main flaws in the referendum proposal is that it would give the new institution unlimited jurisdiction. This was made clear on January 23 by Noel Pearson, one of the key proponents of the voice. He told Patricia Karvelas on ABC radio:

“There is hardly any subject matter that indigenous people would not be affected by and would not want to provide their advice to parliament.”

Indigenous constitutional lawyer Megan Davis, who helped develop the voice proposal, shares this view. On December 21 last year she was asked on ABC television what issues indigenous Australians wanted to talk about to parliament through the voice.

Davis’s answer: “At this point, virtually every issue. The Commonwealth – and cascading through the federation to the states and territories – will be compelled to listen. That’s the key thing,” Davis said.

The preliminary wording of the proposed constitutional provision shows that the scope of the voice would not be limited to indigenous affairs such as land rights.

It would be free to involve itself in any debate that affects the broader community so long as it also relates to Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders.

It is simply incorrect to assert that if this referendum succeeds, parliament could fill in the details later and confine the reach of the voice to matters that relate only to Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders.

Such a restriction would risk being struck down as inconsistent with the words of the constitutional provision which contain no such restrictions.

The prime minister (Albo) unveiled the preliminary wording of this provision in July, 2022, at the Garma cultural festival in Arnhem Land. The second sentence of that three-sentence provision says:

“The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice may make representations to Parliament and the executive government on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.”

So what would this include? Native title to land clearly relates to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – but so does taxation and economic policy. Indigenous people pay taxes and are affected by economic policy.

The involvement of the voice would be triggered by the existence of a matter that relates to indigenous people. The fact that such a matter might primarily relate to the broader community would be irrelevant. If it relates to indigenous people as well, the voice could have a role.

This was clearly intentional.

If those responsible for this provision had wanted to confine the voice to indigenous affairs, or to matters that relate only to indigenous people or even primarily to indigenous people, they would have included such qualifications in the provision unveiled in July. That was not done and it would be too late to revisit this issue if the referendum succeeds.

Conclusion

There is one inescapable fact about modern Australia that explains why indigenous people do not need a separate institution in order to make their views clear to parliament: The proportion of seats in federal parliament held by indigenous Australians is already greater than their proportion of the nation’s population.

Figures compiled by the Parliamentary Library in August, 2022, show Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders make up 4.8 per cent of the members of federal parliament, and just 3.2 per cent of the total population.

Their voices led the debate over the breakdown of law and order in Alice Springs.

This referendum should be rejected – not just because it is wrong in principle but because the proponents of this change have declined to provide the community with enough information to make a fully informed decision.

The government bears the onus of explaining the requirements, implications and restrictions that would arise from the proposed constitutional provision. That requires the publication of independent legal advice on the proposed provision – preferably from Solicitor-General Stephen Donaghue rather than those associated with the “yes” case.

That has not happened.

This is quite apart from the failure to provide an outline of the statute that would create the new entity if the referendum succeeds. Requiring such information is not unreasonable, nor is it racist.

These failures are a departure from normal practice and should not be rewarded. They show insufficient respect for the fact that the Constitution draws its legitimacy not from politicians and insiders but from the entire community.

We are being asked to abandon equality of citizenship – one of our most important values – in order to insert a divisive institution into our system of governance while having only a limited idea about its structure and powers, how it would change the business of government and the implications that could be read into the new provision by the High Court.

This referendum should be rejected – primarily because it is wrong in principle but also because the proponents of this change have failed to provide the community with enough information to make a fully informed decision.

They have forgotten that the Constitution draws its legitimacy from the entire community – not from politicians and insiders.

‘No’ means no: the sensible case against the Voice (Mark Powell, 8 February 2023, The Spectator)

Anthony Albanese’s first act as Prime Minister was to replace two of the three Australian flags in the Parliament House (Media) Blue Room, with an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ensign.

Significantly, the Aboriginal Flag was placed in the centre with the Australian flag off to one side. Mr Albanese then opened with the following commitment:

‘I begin by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land on we meet. I pay my respects to their elders past, present and emerging. And on behalf of the Australian Labor Party, I commit to the Uluru Statement from the Heart (TUSH) in full.’

Welcome to country Australia

They may be thinking more with their hearts rather than their heads. There are a great many problems with adopting TUSH as a progressive political policy. What follows are twelve of the most pertinent reasons for rejecting it:

It does not define its function, powers, and processes.

Under the FAQ’s section on the TUSH website titled, ‘Why a constitutionally enshrined Voice?’ the organisation states:

‘The Uluru Statement does not detail the structure of the Voice and how it will do its job… The details including the functions, powers and processes of the Voice, will be worked out between government and First Nations and put into legislation.’

What will be the function and power of TUSH? Not even the advocates and designers of the statement know. It has no discernible limits. How can the government accept a constitutionally enshrined proposal without knowing what it will actually involve? TUSH advocates must provide a clear analysis of the functions, powers, and processes of the Voice before putting it into something as permanent as the Constitution.

Professor Megan Davis from UNSW argues in a webinar on the TUSH website that it will force the government to listen to the constitutionally enshrined body, because in the past advisory bodies could be ignored. Legally, it is unclear what exactly being ‘forced’ and ‘listened to’ will mean in practice. Could the government reject proposed legislation offered by the Voice to Parliament, or will it act as a fourth body of the State?

It will enshrine ‘race’ into the Constitution.

In 2013 leading Australian anthropologist, Peter Sutton, argued against the concept of a national treaty as he believed that it would lead to a constitutional enshrinement of race. (True reconciliation requires a treaty.) Sutton also persuasively argues that making a treaty that is based on racial identity would exclude family communities of bi-racial descent, and would divide people over the colour of their skin.

It cannot be assumed that a treaty that would differentiate between racial groups would not be abused in 100 years time by future Australians. It will perpetuate the failures of ATSIC.

TUSH draws a direct line between the Voice to Parliament and The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC). On the TUSH website, it argues:

The Uluru Statement calls for a Voice to Parliament to be enshrined in the Australian Constitution by way of an enabling provision. Previous First Nations’ representative bodies (such as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission ATSIC), were set up administratively or by legislation.

That meant they were easily abolished by successive governments depending on their priorities.

Setting up and then abolishing representative bodies cuts across progress, damages working relationships and wastes talent that could be used to solve complex problems.

ATSIC was set up under the Hawke government in March 1990, which established a group of elected individuals to oversee and inform legislation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The statement assumes the abolition of ATSIC was damaging to ‘progress’ and ‘relationships’. This was not the case. ATSIC was abolished because of a series of accusations of embezzlement, corruption, obstruction of police, and rape charges.

Additionally, a government review of the program called, In the Hands of the Regions found it was detached from local communities and was failing to implement successful changes on a regional level.

Because of these ongoing scandals and alleged misallocated funding, the proposal to end ATSIC received bi-partisan support when John Howard announced its termination on April 15, 2004.

TUSH goes one step further. Not only will it repeat the same mistakes as ATSIC by being detached from local communities, it will make these changes constitutionally enshrined and difficult – if not impossible – to abolish.

TUSH will likely become permanent, regardless of any future or potential complaints of corruption, embezzlement, and legal malpractice that may arise. More importantly, it will repeat the failure of ATSIC in nationalising a complex issue that should be addressed by local communities and existing government entities.

It will distort Section 116 of the Constitution which forbids the setting up of any established religious institution.

While this point may not seem immediately pertinent, one of the most significant problems with TUSH is its promotion of Indigenous spirituality (pantheism) in such a way as to confuse the traditional delineation between Church and State. In arguing that ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations’’ the statement defines ‘sovereignty’ in an explicitly religious way:

This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors.

This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, or sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.

TUSH disingenuously states that sovereignty for them is a ‘spiritual notion’. This is because Aboriginal spirituality views Indigenous peoples as eternally connected to the Land and also Peoples. The statement also avoids the complexity of Aboriginal spirituality and views land ownership through a Eurocentric lens, as leading anthropologist A. P. Elkin notes,

It is true, at least from our point of view, that members of such a local group owned their ‘country’. But that is only one aspect of the situation.

A more significant aspect is that they belonged to their ‘country’ – that it owned them; it knew them and gave them sustenance and life. Their spirits had pre-existed in it – in the Dreaming. Therefore, no other ‘country’, never mind how fertile, could be their country nor mean the same.

All of this is in stark contrast – indeed, contradiction – to what is said at the end of the paragraph relating to the ‘sovereignty of the Crown’. These are two distinct claims to sovereignty with different views on spiritual ownership, blurring the line between the church and state.

It will pervert our view of race relations.

TUSH presents a Cultural Marxist paradigm of race based upon an imbalance of ‘power’ and ‘struggle’. Note the Marxist language that TUSH itself uses and highlights:

These dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. This is the torment of our powerlessness.

We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country. When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish.

When race relations are constrained and distorted by a paradigm of power, the disadvantaged race cannot achieve justice until the balance of power is equalised, whether or not the ‘payment’ has been made. The Co-founder of TUSH Professor Megan Davis who is a proponent of intersectionality, argues on the statement’s Facebook page:

The political elite cannot consign the First Nations people to another decade of inaction… without addressing power structures.

What’s more, by placing the blame on an abstract political elite, it takes away the personal responsibility of individuals to deal with their own situation.

It will diminish the moral agency of Aboriginal people.

Following on from the previous point, TUSH seeks to project all current social problems that exist within Indigenous communities onto how they were treated by Europeans historically. This means that Aboriginal people are merely victims of previous injustices. As the statement says:

Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people. Our children are alienated from their families at unprecedented rates. This cannot be because we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers.

While this argument might be popular, it infantilises people with an Indigenous background in such a way that they do not become responsible for themselves. Decades of anthropological research show socialisation, cultural behaviours, and custodial relationships have had a greater impact on Indigenous ‘disadvantage’ than dispossession.

For example, a reduction in serious health outcomes is not the result of a restricted ‘Voice’ to Parliament, but the lack of practical behaviours that could be implemented to close the gap:

These behaviours include absolutely basic things like domestic sanitation and personal hygiene, housing density, diet, the care of children and the elderly, gender relationships, alcohol and drug use, conflict resolution, the social acceptability of violence, cultural norms to do with expression of the emotions, the relative value placed on physical wellbeing, attitudes to learning new information, and attitudes to making changes in health-related behaviour.

Arguing that history and structural racism are the cause for high youth detention rates, community homicides, and increasing levels of incarceration takes away the individual’s culpability.

It will result in racial division rather than produce reconciliation.

TUSH repeatedly invokes the Aboriginal concept of ‘makarrata’ which is based more upon a notion of what Peter Sutton in his book, The Politics of Suffering (MUP. 2009) refers to as ‘ritualised revenge’, in comparison to European notions of restorative, or even retributive justice. As the statement itself says:

Makarrata is the culmination of our agenda: the coming together after a struggle.

We seek a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations.

The concept of ‘makarrata’ though, is more far-reaching than TUSH would lead the uninitiated reader to believe. According to Luke Pearson, writing for the ABC: ‘Makarrata’ literally means a spear penetrating, usually the thigh, of a person that has done wrong.’

Ken Maddock, a specialist in the field of Aboriginal customary law wrote back in 2001:

It would be too strong to say that Aboriginal customary law is getting a bad reputation even among those who have been seen as its natural defenders. But its real or imagined drawbacks are being exposed in a way which is new at the very time that demands are being made for its recognition as a component of a treaty, as a technique of ‘reconciliation’ or as a remedy for the ills of Aboriginal society. Unless some hard thinking is done about what customary law is and what its recognition would entail, any political initiative in its favour may end in tears and disillusion.

It does not offer any objective solutions.

TUSH creates a false correlation with the desired outcome of reconciliation and the proposed solution of a Voice to Parliament. The statement does this by employing vague terminology such as ‘Substantive’ and ‘Structural reform’, which assumes that Aboriginal people must be liberated from systemically racist constraints. But what does that mean and how will such reform take place? The authors of the statement do not go into any detail.

The statement also claims to engage in ‘Truth-Telling’. Behind this particular truism is a loaded assumption that the political and historical viewpoint of the organisation alone has a monopoly on the ‘truth’. Similarly, statements like seeking ‘fair and truthful relationships’ supposes race relationships are somehow not currently ‘fair’ and ‘truthful’, furthering the cause of racial division.

Most importantly, the statement is ‘from the heart’ – terminology assumes the moral high ground.

It will undermine the three existing arms of government.

The current Constitution of Australia involves three distinct but complementary limbs of government: the legislative (Parliament), the judiciary (Courts), and the executive (The Queen, through her representative the Governor-General). However, TUSH seeks to introduce a fourth arm into this mix: an Indigenous Voice, with substantive constitutional change and structural reform.

While this might seem noble, it is not clear how this fourth component will work in with the existing three. Aboriginal people already have a voice as citizens and legal voters. In addition, there have been several major Royal commissions into Indigenous issues from:

• Aboriginal Deaths in Custody: The Royal Commission and its Records, 1987–1991.

• Indigenous Deaths in Custody 1989-1996.

• Bringing them Home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families.

• HEALING: A Legacy of Generations (Report on the Stolen Generation Inquiry, 2000).

• Unfinished Business: Indigenous Stolen Wages (Report of the Inquiry into Stolen Wages, 2006).

• Doing Time – Time For Doing: Indigenous youth in the criminal justice system.

• Pathways to Justice–Inquiry into the Incarceration Rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (ALRC Report 133, 2018).

The government has a minister from Aboriginal Australians, Linda Burney. The truth is, Aboriginal Australians are well represented in our democracy.

It will re-frame our understanding of history.

TUSH claims to ‘seek … truth-telling about our history’. But what is the ‘truth’ of history that TUSH argues is being suppressed? The TUSH website gives away its progressive ideological agenda when it states:

Australia must acknowledge its history, its true history. Not Captain Cook. What happened all across Australia: the massacres and the wars. If that were taught in schools, we might have one nation, where we are all together.

Is Captain Cook not a part of Australia’s true history? The TUSH Facebook page also uses the hashtag #HistoryIsCalling, in a revisionist attempt to rewrite Australian history as a struggle between racial groups. The past should not be governed by a political organisation, but should instead reflect the complex process of historical inquiry which is open for all people to investigate together. If this racialised view of history is ‘taught in schools’ without a balanced perspective of British settlement, it is hard to imagine a nation that can truly ‘come together’ under TUSH’s one-sided historical ‘truth’.

The TUSH website also claims:

The Tasmanian Genocide and the Black War waged by the colonists reveals the truth about this evil time. We acknowledge the resistance of the remaining First Nations people in Tasmania who survived the onslaught.

The statement assumes this is the only ‘true’ interpretation of history, ignoring three key facts about Tasmanian history: there were around 118 recorded deaths of Aboriginal people from 1803-1847, which is lower than those of the white settlers killed; the Tasmanian government had an active policy of goodwill towards the Indigenous population; and the decline in the Aboriginal population is mainly attributable to European diseases, the treatment of women, and inter-tribal violence. The settlers were not all malicious types who wanted to dispossess, murder, and pillage.

It will nationalise an Issue that should remain localised.

A national treaty will not address the local issues of Aboriginal communities. In fact, it would not make sense to have a national treaty for a people group that is not ‘one’ nation. Alternatively, Native Title treaties rely on an evidence-based approach to the traditional land tenure of modern Aboriginal descendants by investigating their complex relationship with resource management and pre-existing claim to Aboriginal sovereignty. Australian Anthropologist Peter Sutton makes several key arguments for regional treaties over constitutional recognition:

Australia already has over 800 regional treaties.

The idea that other countries like New Zealand and Canada have a treaty with every Indigenous person is not true. They have specific treaties with specific tribes, as in Australia.

Some states such as South Australia are made up of 39 per cent Native Title land organised by treaties and the Northern Territory is not far behind.

Each of these treaties has been planned in accordance with regional groups and suited to the needs of the particular community.

Land granted through each Native Title treaty in each state has not made a clear difference in social outcomes on a national level.

There is no standard of post-colonial treaties because there is no single national treaty in the world that recognises every native group in every part of a country.

The crimes of the past cannot be solved by a national treaty, and the disadvantages of the past and present are not changed by a national treaty.

It will not resolve the real problems Indigenous peoples face.

By far the most significant failing of TUSH is its inability to make any real difference to the lives of Aboriginal peoples. As Keith Windschuttle argues in Quadrant:

There is no credible empirical evidence that mention¬ing Aborigi¬nes in the Constitu¬tion would improve their health. The claim is spec¬ula¬tion by a lobby group of psy¬chiatrists, who claim it would improve Abo¬riginal self-esteem. The gesture would be largely irrelevant to the 80 percent of Aboriginal people who are now well inte¬grated into mainstream Australia, mostly in the suburbs of the major cities and larger regional centres. And it would go com¬pletely unnoticed in the emergency departments of hospitals in central and northern Australia where, because of the failed policy of isolating indigenous people in remote communities, Abo¬riginal women and child victims of Aboriginal violence and sexual abuse are grossly over-represented.

Indeed, some academics such as Germaine Greer have gone as far to explain the high rates of domestic violence from Aboriginal men as repressed rage against the disempowerment by white people, taken out on their wives and children. This type of victimhood blaming requires the minority group to remain victims. A murdered woman is not ‘disadvantaged’; she has lost her life. As the eminent epidemiologist Stephen Kunitz put it;

To suggest that pre-contact Indigenous life was anything but Edenic and that traditional modes of socialisation and social control may contribute to the contemporary problem of violence is to risk being accused of blaming the victims and excusing their oppressors.

Indigenous Australians themselves have proposed much better solutions to welfare dependency, substance abuse, life expectancy, declining literacy, violence against women, and child sexual abuse. These include integration into urban economies, stronger engagement in Australian education, dietary intervention, coercive crime control, alcohol limitation, resettlement from regional areas, and even conversion to evangelical Christianity.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart (TUSH) will not unite Australians, but only divide us. It will not address the many real needs that indigenous peoples face on a day-to-day basis, and as such, it should be firmly rejected as a way forward. And that’s because it’s an attempt to undermine decision-making and due process in a western democracy that already affords aboriginal political representation. Ultimately, TUSH is a take-over by stealth and manipulation through preying on our feelings of guilt.

Is English the next victim of THE RACIST VOICE secret agenda – to be banned in Australia and supplanted by one of the 500 Aboriginal languages? Which one?