Not The Voice, but elitist Aboriginal separatist SCREAM!

Voice or sovereignty: Lidia Thorpe has revealed the real Blak agenda (Peta Credlin, 9 February 2023)

The defection from the Greens of Senator Lidia Thorpe was so much more than your stock-standard act of political betrayal. It has provided a window into the real agenda behind the proposed voice, which is much more about who really owns Australia than it is about recognition and consultation.

Labor Prime Minister Anthony Albanese keeps saying the voice is no more than a “modest but meaningful” change about being polite to the First Australians.

What he doesn’t say is that the voice is just one element in the demands of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, to which he and his government are fully committed. As recently as last weekend, at the Chifley Research Centre, he said: “I am proud to lead a government committed to the Uluru Statement from the Heart in full.”

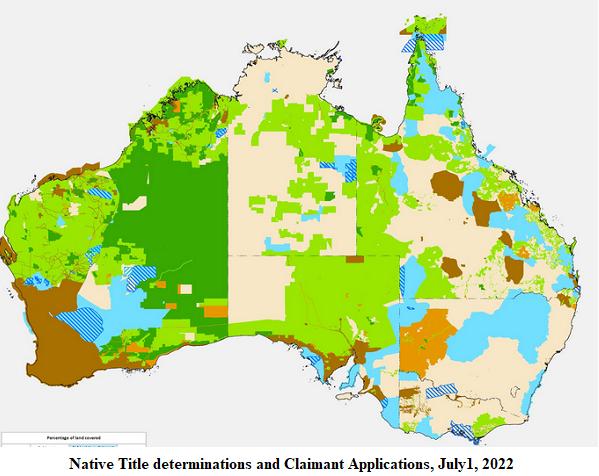

The Uluru Statement expressly states “our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign nations of the Australian continent” and that “this sovereignty … has never been ceded or extinguished”. According to the statement, its signatories don’t just want a voice enshrined in the Constitution; they want what they call a “Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations and truth telling about history”.

So the argument between Lidia Thorpe and the Greens is about means, not ends; it’s about what comes first: voice or treaty. Thorpe says that accepting the voice prejudices the call for sovereignty. The rest of the Greens say (and the Albanese government never contradicts them) that the voice is just the first step towards the treaties that will eventually enshrine Aboriginal sovereignty and forever change the broader concept of Australian sovereignty for everyone else. Indeed, that’s exactly what Adam Bandt, the Greens leader, declared on Monday: that he’s supporting the voice precisely because he had received “guarantees” from the government “on sovereignty and funding to progress treaty and truth”.

When the PM was asked about sovereignty at the weekend, he left the door open on Indigenous claims; he certainly didn’t state that any Indigenous sovereignty had been extinguished by the settlement of Australia or by the growth over two centuries of the migrant population. Instead, he danced around it, saying that the referendum will have “no impact on the issue of sovereignty”.

But that’s not what his senior colleagues think. Labor senator Pat Dodson has said at various times that the whole point of the voice is that “we are seeking recognition of our sovereign status” and that the voice is about “addressing the tyranny of Indigenous dispossession”. Then there’s Labor’s Senator Malarndirri McCarthy who recently said: “We’ve never ceded sovereignty, and do you think I’d stand by and let that happen?”

No one should be surprised the PM is trying to square the circle between Indigenous activists who want the voice to rewrite history, as if the British and 25 million others hadn’t come here starting 250 years back; and those people whose ancestry doesn’t extend back beyond 1788 and who won’t appreciate being told they’re lesser Australians. The surprise is that Albanese is being allowed to get away with reassurances that simply don’t add up.

As the historian and editor Keith Windschuttle has pointed out, the coming referendum should not be seen “merely as a sympathetic means of eroding the marginality of Indigenous people in remote communities but as a potential threat to Australia’s unique geographic and political status”.

He says, in an article in the September 2022 edition of Quadrant magazine, that the Indigenous activist class simply won’t accept their position as just another minority group in a diverse society – “its members want political power commensurate, not with their numbers in the population, but with the fact that they got here first”.

To the activist class, he says, “closing the gap” has never really been about improving the lot of poor Aboriginal people but about re-establishing Indigenous people as the rightful possessors and titleholders to Australia.

Far from being against Indigenous sovereignty, the green-Labor alliance wants to entrench it, with ever more race-based separatism, on the understanding that Indigenous people have so far come off worse in the clash of civilisations.

As early as 1982, the nationally elected National Aboriginal Conference declared that sovereignty required the eventual establishment of “Aboriginal states” that would evolve into “separate nations”. “The status thus created would be an interim for as long as the Aboriginal nation needed to evolve to the point of being able to exercise the right of self-determination”.

A close inspection of what’s under way across the Tasman is illustrative of the activists’ co-governance endgame.

As Windschuttle says, voters in the referendum should “recognise that its ultimate objective is the establishment of a politically separate race of people and the potential break up of Australia”.

Hence the question: precisely what guarantees has the government given to the Greens, as affirmed by Bandt, on sovereignty, on treaty and on truth?

And what promises have been made to Aboriginal leaders like Dodson? On all these questions, the PM is increasingly slippery. Perhaps because he knows only too well that if he answers them in a way that would satisfy the green-left, he would also reveal to voters this voice is a Trojan Horse to change Australia forever.

Fundamentally, what’s at stake in this debate is: who really runs Australia? Is it the parliament elected by all Australian citizens; or is it the parliament, provided the 800,000 Indigenous people represented by the voice don’t object?

The Blak Sovereign Movement that Senator Thorpe says she now represents wants every homeowner to pay 1 per cent of wages to the relevant Indigenous body as a tax or rent to the original inhabitants whom, she says, are still really the current legal owners of Australia. According to Thorpe, those who came since 1788, and their descendants, are permissive tenants only with no absolute right to be here.

How’s that for creating two classes of citizen based on people’s ancestry?

If nothing else, it undermines the decades-old multicultural push that newly arrived Australians are just as much citizens of this country as those with convict-era heritage.

Should this voice pass, be under no illusion about what will then happen: Australia Day will change; there will be more demands to rewrite history; and there will be a multitude of treaties at all levels of government between our country and small groups of its citizens.

Australia Day – anniversaries of civilizing Aboriginal barbarism

And ultimately, there will be demands for more payments from taxpayers to Aboriginal Australians – on top of the $30 billion a year that the Productivity Commission estimates is currently spent on Indigenous programmes.

To be clear, it’s not the spending I begrudge but the lack of outcomes tied to it, and the industry that’s grown up around the suffering of mainly women and children in remote communities that seem perversely incentivised for the suffering to continue in order to secure their next round of funding.

By blowing up the sovereignty issue this week, Thorpe might have inadvertently shaken voters out of their complacency.

The voice is not just about being polite and respectful to Aboriginal people. It’s about whether Australia belongs to all of us – or to just some of us – with the rest of us being barely tolerated interlopers.

(Political Reporter Sarah Ison & Indigenous Affairs Correspondent Paige Taylor, 31 March 2023)

Professor Megan Davis declares: ‘you won’t shut the Indigenous voice to parliament up’

Parliament will not be able to “shut the voice up” and the Indigenous body will speak to “all parts of the government” including the cabinet, ministers, public servants as well as statutory offices and agencies from the Reserve Bank to Centrelink, according to top referendum working group member Megan Davis.

A key architect of the Uluru Statement From the Heart and one of six members of the working group that negotiated the final wording of the constitutional amendment with the government, Professor Davis said parliament could not stop the voice from making representations or “shut the voice up”.

Uluru Statement from the Rock is a Croc!

The clarification on the broad remit of the Indigenous voice comes after Anthony Albanese this week argued that parliament would have primacy over “what the voice will consider” – a remark that was corrected by legal experts who explained this would be beyond the reach of politicians.

Labor members of a new parliamentary committee testing the wording of the Prime Minister’s proposed constitutional amendment said they hoped the inquiry would rebuff criticisms from “naysayers and doomsayers” and bolster the Yes campaign.

Noel Pearson, a champion of constitutional recognition for Indigenous Australians, said he was confident the nation was heading towards success and that negotiations over the wording of the constitutional amendment had “landed in a very sweet spot”.

Mr Pearson said Professor Davis had “always been our leader in relation to the constitutional law” and was “our most expert spokesman on the drafting.”

Professor Davis and fellow constitutional law expert Gabrielle Appleby from UNSW, writing in The Weekend Australian, argue that the new body will not be “limited to matters specifically or directly related to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples” and it will have the power to “speak on a broad range of matters”.

“That is the point,” the professors write.

Professor Davis, UNSW’s Balnaves chair in constitutional law, and Professor Appleby say the voice could advise government across the policy spectrum from environment and climate to defence or financial matters, but stress that it should choose where it makes its representations carefully.

“It would include matters relating to the conduct of elections, given the under-enrolment of First Nations people in our electoral system,” they say.

“It would include criminal matters, given the over-representation of First Nations in our criminal justice system.

“It’s important that the voice speaks not just on matters that directly, or explicitly, affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, but on matters that have an indirect but significant effect on them.”

The pair say that, if the voice speaks on more general matters, such as financial policy or defence, its representations will be “weighed up against a number of other interests and groups” and have less political persuasion. “It will have to spend its political capital wisely,” the professors write.

“The voice will be able to speak to all parts of the government, including the cabinet, ministers, public servants, and independent statutory offices and agencies – such as the Reserve Bank, as well as a wide array of other agencies including, to name a few, Centrelink, the Great Barrier Marine Park Authority and the Ombudsman – on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

“This isn’t to be feared.”

The Coalition is concerned by the wording in the constitutional amendment that gives the voice the power to advise the executive government.

Leading Liberal moderate Simon Birmingham signalled his hope for this to be reconsidered in the parliamentary committee process. “By putting it in the Constitution, it does then provide another layer of wording that can be contested through High Court challenges where constitutional challenges are heard,” Senator Birmingham told the ABC.

Labor MP Shayne Neumann, who has been appointed to the committee, said the inquiry should help to smooth over concerns with the existing wording.

“I hope the naysayers and doomsayers and people engaged in jeremiads will have that information rebutted in the course of this inquiry,” Mr Neumann said.

Liberal committee member Keith Wolahan said the inquiry was as close to a “constitutional convention” as the nation would get. “The committee should waste no time in properly testing the wording and exploring in an honest way all of the constitutional risk that should be considered – and there’s certainly constitutional risk in that wording,” Mr Wolahan said.

South Australian Liberal senator Kerrynne Liddle, another member of the committee, said the inquiry needed to provide for a range of voices to be heard, including controversial figures such as Human Rights Commissioner Lorraine Finlay who faced a backlash against her concerns over the voice this week.

Ms Finlay, who was appointed to her role by the Morrison government and a former Liberal candidate, wrote in The Australian this week that the new constitutional amendment went beyond the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and possibly conflicted with other international human rights agreements.

Senator Liddle said Ms Finlay was entitled to her views and was “hopeful that people like commissioner Finlay would feel comfortable expressing their view in what would be a safe, respectful environment to do so”.

Victorian Labor senator and committee member Jana Stewart said she hoped to see “a broad representation of witnesses appear before the committee”.

“I hope to see respectful and robust conversation. The Australian people deserve nothing less,” she said.

Committee members said key players in the national debate over the voice — including Mr Pearson, Professor Davis and other legal experts – should appear before the inquiry to have their arguments “explored and tested”.

In their piece, Professor Appleby and Professor Davis said the broad remit of the voice would restrict rather than increase the chance of legal challenges.

Court in the act: what else is voice lobby not telling us?, Janet Albrechtsen, 1 March 2023

Has there ever been a more flagrant attempt to deceive the Australian people than the Albanese government’s effort to force-feed the voice into our Constitution?

Aided and abetted by an army of activist advisers and cheerleaders, Anthony Albanese and Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney lead what can only be described as the great deception.

The root cause of this deception is that the objective of this campaign is to enact a massive change to our constitutional arrangements, namely to begin the process of replacing our long-treasured sole and exclusive sovereignty of the crown with the form of co-sovereignty between the crown and Indigenous Australia demanded by the Uluru Statement from the Heart. This, in turn, is a first step to treaty and self-determination.

This radical step could be implemented only by pretending the change was modest, encasing it with feel-good atmospherics, backed up with frequent browbeating.

What, for example, is law professor Megan Davis doing by demanding universities, including the peak body, Universities Australia, sing from her Yes song sheet? Universities are meant to encourage free thought, not foisted views, aren’t they?

The gamble by Yes activists that we would not look too hard at the proposed wording and its consequences, or stand up to bullying, has manifestly failed – to the point where even some voice supporters are now coming clean.

The result: the Yes campaign is now falling apart under the weight of its internal inconsistencies, dishonesties and division.

Who could forget that the Prime Minister’s much-quoted Calma-Langton report promised us, in section 2.9, that their Yes model would “reflect the need to respect parliamentary sovereignty and avoid causing unintended consequences. As a result, all elements would be non-justiciable, meaning that there could not be a court challenge”?

There was a time when many voice supporters recognised that non-justiciability was critical: to avoid opening a massive hole in parliamentary supremacy and creating a huge transfer of power from our elected parliament to unelected courts.

Pointing the Bone at anything that challenges the elitist Aboriginal inner circle

Not so any more. Now, Langton admits the voice is a matter for the courts. On ABC radio recently she said: “Why would we restrict the voice to representations that can’t be challenged in court?”

Asked about whether High Court challenges could be used to delay government decisions until the voice had deliberated on the matter, Langton said, “That’s a possibility … why wouldn’t we want that to be the case?”

Many curiously minded and in some instances legally trained commentators have consistently warned the voice would be able to use leverage extracted by lawsuits to gum up the processes of government, and thereby hand vast negotiating power to the voice and its supporters. We were naysaid and insulted by a phalanx of activist lawyers.

Constitutional lawyer Greg Craven said “this legal fright-fest is bizarre” as he assured us that the High Court would not, for example, impose legal obligations around consultation with the voice.

Traditional Aboriginal Justice – spearing

The gap between then and now is remarkable and of concern. Since then, former High Court justice Kenneth Hayne admitted the voice could be the subject of litigation, but he told us to trust the courts. Then fellow former High Court justice Ian Callinan confirmed the voice could be the subject of a decade of litigation. He appeared less trusting of the courts. Now, even ardent voice supporter George Williams has admitted what he should have told us upfront. “Courts will play a role in the operation of the voice,” he said recently.

Last December, Williams wrote: “There is no requirement the voice be listened to before a decision” was made. Last week, Williams admitted: “Courts may be asked to rule on the … the consequences of a minister failing to listen when the voice has spoken.”

Other leading figures in the Constitutional Expert Group such as constitutional lawyer Davis, as well as Craven, have also recently acknowledged what was long denied or dismissed – namely that the courts will play a significant role in determining the powers, processes and functions of the voice.

Why didn’t all these lawyers tell us this earlier? Why did this entirely logical consequence of a constitutionally entrenched voice have to be effectively flushed out of them? What else are they not telling us? Are they saving future surprises for us, to be revealed only if a Yes vote is successful?

Craven is at least honest about the political power handed to the voice by the possibility of lawfare. He now publicly admits to the legal issues rising from the voice. “Politically and practically, delay (from litigation) often means death to proposed action,” he conceded recently.

It’s high time the PM came clean, too, and admitted what Williams, Davis, Craven, Langton and a couple of High Court judges now tell us: the power of the voice, at law, to delay, hinder and litigate gives it a potent veto in practice.

Given the sudden shifts from high-profile voice activists saying one thing last year, then another more recently, we have every reason to ask: when will the con job on the Australian people end?

For many years, constitutional lawyer and academic Shireen Morris has assured us that “a First Nations voice was specifically designed to be non-justifiable”.

That became a fiction the moment the Prime Minister released the words of his Albanese amendment at Garma last July. Surely it is time that Morris too admits that non-justiciability is a myth.

Likewise, we could ask the well-regarded constitutional lawyer and academic Anne Twomey whether she has done enough to ensure the Australian people are fully informed about the legal impact of the voice on parliamentary sovereignty.

Perhaps most disappointing among this cast of Yes lawyers is opposition legal affairs spokesman Julian Leeser. If Noel Pearson is right that Leeser, along with Craven and other so-called constitutional conservatives, agreed the earlier wording on which the Albanese amendment is modelled, then Leeser has been guilty of naivety – at best.

Pearson is entitled to be miffed, and so are Liberals who are deeply opposed to a race-based constitutionally entrenched body that would up-end our governance.

Let’s return to the fundamental problem. This is no “modest proposal” but a carefully crafted attempt to replace crown sovereignty, the sovereignty of all of us, with the co-sovereignty demanded by the Uluru statement. Armies of activists and academic lawyers have been beavering away for years trying to find ways of inserting into our Constitution the wedge that leads to this co-sovereignty.

Either Leeser is a fool or he understands this.

It has become crystal clear that deception, dissembling and intimidation have been key to the whole campaign. Now, with significant parts of the great deception exposed, unwittingly, by these same voice activists, we are entitled to ask: what more haven’t they told us?

Indigenous voice risks perpetuating a long history of failure, Jacinta Nampijinpa Price is a Country Liberal Party senator for the Northern Territory, 4 March 2023

In Noel Pearson’s recent article in The Weekend Australian, “Conservatives eat their own words on voice” (25-26/2), he argues the concept was born from constitutional conservatives who he now describes as characteristically “fickle”.

The concept may have begun in 2014 as a collaboration between constitutional conservatives and Indigenous leaders but with the help of a senior adviser on the voice committee, Marcia Langton, it has morphed into an entity she argues should compel government to listen to it, otherwise it would be a “toothless tiger”.

Contrary to Anthony Albanese’s suggestion that it wouldn’t have the power to challenge government in the High Court, Langton is adamant that is exactly what it should be able to do.

No constitutional conservative in their right mind could now support such a concept. Pearson might find it cathartic of the voice, but his comments fail to argue what he perceives to be the merits of this gargantuan race-based constitutional change.

He once supported my fight to maintain the cashless debit card for vulnerable Australians – now abolished by the government he supports on the voice. He has since publicly denigrated my opposition to the voice.

At least the conservatives he has expressed disappointment in provide a sound argument to the dangers of the Yes vote; as opposed to making personal attacks.

Contrary to the argument by voice proponents that Aboriginal Australia has been “voiceless” and needs an overarching entity to hold parliament and executive government to account, Pearson himself is among those who have had a seat at the table for decades.

He has been a key player in the Indigenous policy space since the early 1990s.

Through the establishment of the Cape York Institute for Policy and Leadership during 2011 to 2016 alone his efforts have attracted more than $47 million in government funding for the design and implementation programmes to advance communities.

Pearson has had the ear of many prime ministers of both Labor and Coalition governments over the decades. His has been a prominent voice to parliament, despite never taking the opportunity to run for a seat himself.

Another proponent of the voice, Pat Turner, who is currently the head of the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations – a body many would consider is a voice to parliament – has also in her own words, “held senior leadership positions in government, business and academia for more than 40 years, and had extensive experience in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs”.

In fact, over those decades her roles included deputy secretary of the Department for Aboriginal Affairs, deputy secretary for Prime Minister and Cabinet which oversaw the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation; chief executive of the now dismantled Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission for four years, senior managerial positions in Centrelink and the Department of Health, and chief executive of the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations body since 2016. As head of NACCHO, Turner has been responsible for the delivery of services to the tune of more than $27 million in White grants funding.

In more recent times, Turner’s influence on federal parliament has ensured a redesigned Closing the Gap process. During the 2023 anniversary of the apology, she presented a fresh set of plans. Addressing the entire senior executive of the Albanese government she exclaimed, “we know that outcomes for our people can be much better when central agencies are playing a leadership role”. With her influence, Turner has convinced the Albanese government to increase investment toward Closing the Gap by $242 million.

She has been a vocal advocate for more financial investment into Aboriginal disadvantage despite the more than $30 billion investment made year in, year out, regardless of who’s in power.

In a recent interview with ABC’s 7.30 Turner argued that governments fail to invest and that a voice to parliament would, “keep on saying what we’ve been saying for decades, ever since we’ve all been involved because of the lack of investment by governments”.

Turner goes on to say that, “having a voice won’t stop the need for the investment by governments in programmes – governments still have to do that”.

In other words, the voice is not a new approach to solving disadvantage but simply the current framework of voices that exist in various different “central agencies”, corporations, advisory committees, land councils – and so on – that will be embedded within our Constitution.

These are examples of merely two influential voices to parliament, but there are many more.

Within parliament itself, four very senior Aboriginal parliamentarians – minister Linda Burney, senator Malarndirri McCarthy, senator Patrick Dodson and member for Lingiari Marion Scrymgour – now argue a constitutional amendment is the answer to Closing the Gap.

What does it tell us that these four members of parliament who have 65 years of collective experience within state, territory and federal parliaments both in opposition and in government as Indigenous Australians now argue a voice to parliament is the only answer?

If we want to make a difference in the lives of our most marginalised, we have to begin by putting a stop to treating Aboriginal Australians differently.

The structures that have existed and failed, despite the billions of dollars of investment, are systems that have been built on the ideological premise that Aboriginal Australians are to be treated differently and separately and are inherently disadvantaged as a result of racial heritage.

The above-mentioned powerful voices are clear evidence that any human who can gain an education can take advantage of what our nation has to offer and this is not a determination of race. None of these leaders required a voice to parliament to succeed.

In 2016, the Centre for Independent Studies uncovered that of 1082 Indigenous-specific programmes identified in a review of government and non-government programmes, only 88 (8 per cent) had been evaluated. And of those programmes that were evaluated, few used methods that actually provided evidence of the programme’s effectiveness.

On the whole, Indigenous evaluations are characterised by a lack of data and an over-reliance on anecdotal evidence.

I will continue to argue that we need to forensically audit the current systems that have been funded to “close the gap” to determine the successes and discard the failures. As long as an industry exists to “close the gap”, the gap will not close.

Constitutionally enshrining the very voices that exist within the structures that perpetuate the ideological notion that Aboriginal Australians are inherently disadvantaged, is constitutionally enshrining failure.

Why the Indigenous voice is a bad idea on so many levels, Gary Johns, Secretary of Recognise A Better Way (The Voice No Case Committee Incorporated), 25 February 2023.

In his victory speech in May last year, Anthony Albanese said: “I commit to the Uluru Statement from the Heart in full.” There are three parts to this commitment – voice, treaty, and truth. The Australian electorate must understand that a vote for the voice is a vote for voice, treaty, and truth.

Recognise a Better Way, like most Australians, has a deep sympathy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. We understand their desire for recognition and for help for those who are in need. Our concern is that the Prime Minister’s proposals as set out in the Uluru statement make the form of recognition far too political and do not address need.

This paper, on the voice, is the first of three analysing the full Uluru package on which Australians will be asked to vote at the coming referendum.

The argument used by the Prime Minister and supporters of the voice goes like this. “The voice will be embedded in the Constitution in a way that the parliament can determine its design, funding and processes, therefore there is no risk that other Australians will be ignored.” But if the voice is to be designed by parliament, and allegedly is subservient to parliament, why not simply establish it by an act of parliament?

Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney said calls for a voice to be legislated ignored “the wishes of the more than 1200 First Nations leaders who took part in nationwide consultations that led to the Uluru statement”. More accurately, the statement was written by a small coterie and presented at Alice Springs to a gathering of 250 delegates sponsored by the commonwealth government’s Referendum Council.

It is not the wishes of a small proportion of the Aboriginal population that counts; it is those of all Australians that counts. In a referendum, it means a majority of votes in a majority of states. Voters may regard the Uluru statement as no more than an ambit claim.

The reason the Prime Minister and his minister do not want a trial of the voice under an act of parliament is that their plan to implement the entirety of the Uluru statement would be strengthened by constitutional change.

They hope to achieve this goal in three steps.

First, a blank cheque strategy. They hope to win the referendum by moral bullying – “do the right thing, you are racist if you don’t” and by minimum exposure – “read the Calma-Langton Report, if you want to know how the voice would work”.

Second, following a successful Yes vote, the Aboriginal leadership would demand the strongest possible powers. With a powerful voice drowning out opposition, and huge public resources, stage three would follow with the full promise of the Uluru statement – a Makarrata Commission for a “treaty”, and “truth-telling” about Aboriginal history.

The reason for the Prime Minister’s reluctance to explain his model is that it is not a simple plea for recognition, it is a step towards a new distribution of political power in Australia. Its effect is to establish a shadow government, with its own advice apparatus to make demands of government and the parliament not available to any other constituency. The Prime Minister makes frequent reference to the Calma-Langton Indigenous Voice Co-design Process Final Report as the model likely to be implemented following a referendum.

The report is an excellent insight into the thinking behind the voice.

It refers not only to the process of giving advice, which already exists throughout the commonwealth government and parliament, but also aims to bind the government and the parliament to “consultation standards” across the entirety of commonwealth public policy for one group, selected by race.

The consultation standards would create political leverage. While the voice would not have a veto over legislation or government policy, it would have a platform on which to trade its ability to delay and grandstand, for votes in the parliament. Politicians would use the voice processes to delay or block government legislation. Senators would trade with the voice to do their bidding.

Such power rewards the powerful, it does not solve problems. It is not voices but different policies that are required to change the lives of the small group of Aboriginal people (perhaps 20 per cent of the Aboriginal population) in need of government assistance. Take, for illustration, two enduring issues in Aboriginal communities – banning alcohol and the Basics Card. Aboriginal people are divided on both issues, for and against banning alcohol, and for and against the Basics Card. More voices saying the same contradictory things does not solve problems.

At a point in time, votes in parliament could be traded by persuading a majority of the voice members to join with a senator or some senators to vote up or vote down a proposition – in return for programmes or other legislative changes favourable to one dominant faction of the Aboriginal voice. That is how politics works. It is the context within which the voice model – the Calma-Langton report – must be understood.

The report is a scheme to have 24 national members selected by Aboriginal groups formed at a regional level, assembling in Canberra on a permanent basis. They are not elected. There is no mechanism for a formal ballot in the model. Members selection would be the result of the endless struggle for preferment within Aboriginal organisations. Sitting behind this political melee and embedded in the report are numerous assumptions. Two crucial ones are:

That recognition solves needs: recognition started as an acknowledgement of Aboriginal occupation prior to European settlement. It has been expanded well beyond recognition to a political instrument to advance sectional interests. The voice would make endless claims against every Australian not of Aboriginal descent. There is no evidence that “recognition” would solve the problems of those in need, or “Close the Gap”.

That Aboriginal people are not heard: Aboriginal people have the right to vote and stand for election. There are 11 members of the parliament of Aboriginal descent. They have created representative organisations since the 1920s. The national voices consist of the Peaks of Aboriginal organisations and statutory authorities. There are scores of land councils, Aboriginal corporations, agreements between traditional owners and governments, and committees of Aboriginal people in every state and local government and major corporations. Would the formal voice override these voices?

The national voice’s 24 members would be “collectively determined’ by 35 local and regional voice groups. The key is that members are selected, not elected. There is no formula as to how a combination of individuals and scores of different Aboriginal organisations come together in regions to choose one delegate as a member of the national voice. As complex as that task is, it could have been simplified by holding an election of all Aboriginal people in a region. A probable reason for not holding elections is the issue of identification, which would require an electoral roll of Aboriginal people. Proof of identity is a real issue in Aboriginal politics.

Nevertheless, the model recommends a delegate selection process which would be told to “navigate their way” between two principles – “inclusive participation” and “cultural leadership”, which would be different in every region. A more befuddled formula to select members of the voice could not be imagined.

Traditional ways of selection are male-dominated and secretive. They are not conducive to ultra-progressive ways of inclusion – LGBTIQ and gender and so on. They are not even conducive to democratic processes. There are likely to be countless legal challenges to the selection of members because of these rules.

The model provides for two members from each state, the NT, ACT and the Torres Strait. A further five members would represent remote areas. This structure suggests that there is awareness that remote areas have little voice or are at most disadvantage. If that is so, why is there a need for an entire shadow government when the real problems exist for one small part of the Aboriginal electorate? It also highlights the problem – what if the NT member is against alcohol bans and the “remote” member is in favour? Whose voice wins?

The national members in all likelihood would be officials of the considerable number of Aboriginal organisations in Australia.

The stranglehold of those in power in Aboriginal organisations would be reinforced and promoted to a national level. Elected members want to get re-elected; to do so, they must reach beyond their organisation to a majority of their constituency. This fundamental truth will be abandoned by the voice method of selection.

The voice would be a new independent commonwealth entity supported by its own Office of the National Voice. There would be a set of consultation standards providing guidance on when, how and on what types of matters the national voice should be consulted by the parliament and government. It would also seek to impose mechanisms on the parliament.

The Calma-Langton claim that “the aim would be to support and not disrupt effective legislative and policy processes” is naive. The claim that “the compliance of the Australian parliament and government with these elements could not be challenged in a court” is disingenuous. Just because Calma-Langton say the matters could not be challenged does not stop them from being challenged. It may take years to settle at law and would be under constant fire when the voice did not get its way.

The Calma-Langton model insists there be no disturbance to existing bodies, committees, and processes. Imagine an Aboriginal organisation comes before a Senate hearing. Does a member of the voice step in as the true representative? Voice members may displace other Aboriginal voices. The thousands of arrangements worked up between Aboriginal people and governments and businesses would be subject to a new layer of politics. Any dissatisfied Aboriginal person having lost out in present arrangements would appeal to their national delegate and start the fight all over again. The Prime Minister is trying to impose on Australians a shadow government based on race. His preferred model for the voice says so.

Welcome to Country