16 Strands for an Harmonious Brexit

Strand 1: Brexit must be implemented by UK Government as Promised.

By a narrow margin, a majority of citizens of the United Kingdom at their democratic request, voted on 23rd June 2016 for the United Kingdom to leave the European Union (EU) under the provisions of the European Union Referendum Act 2015. This entails the UK exiting both the Single Market and the Customs Union – hence ‘Brexit’.

Brits want to do this to escape from EU onerous rules and undemocratic regulations and the imperial jurisdiction of the European Court – which presumes it can control the movement of people into the UK – notably unfettered welfare immigration from an incompatible Third World.

Although legally the referendum was non-binding, the government of that time had promised to implement the result, and it initiated the official EU withdrawal process on 29 March 2017 by the UK government then invoking Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union on 29 March 2017.

The set period for negotiating a withdrawal agreement will end unless an extension is agreed which put the UK on course to leave the EU by 30 March 2019.

Brexit is a call to action by the British people demanded of the UK government. It is incumbent upon the government to fully implement what has become known as ‘Brexit’ and within the timeframe and by the deadline promised.

Strand 2: Recognise the Purpose and Promises of the EU Membership.

The European Union was initially formed in the aftermath of World War II as the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1950. The ECSC was first proposed by French foreign minister Robert Schuman on 9 May 1950 as a way to prevent further war between France and Germany. He declared his aim was to “make war not only unthinkable but materially impossible” which was to be achieved by regional integration, of which the ECSC was the first step. The Treaty would create a common market for coal and steel among its member states which served to neutralise competition between European nations over natural resources, particularly in the Ruhrgebiet.

The ECSC was an organisation of six European countries created after World War II to regulate their industrial production under a centralised authority. It was formally established in 1951 by the Treaty of Paris, signed by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany.

The ECSC was the first international organisation to be based on the principles of supranationalism, and started the process of formal integration which became a forerunner of the European Economic Community. The European Union was established under its current name in 1993 following the Maastricht Treaty of 1992.

The fundamental purposes of the European Union are to promote greater social, political and economic harmony among the nations of Western Europe. The EU reasons that nations whose economies are interdependent are less likely to engage in conflict.

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organisation which aimed to bring about economic integration among its member states. It was created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957. The Community’s initial aim was to bring about economic integration including a common market and customs union with a common external tariff; common policies for agriculture, transport and trade, including standardization, a single Euro currency, eventually single European citizenship, and mutual prosperity by its member countries.

Upon the formation of the European Union (EU) in 1993, the EEC was incorporated and renamed as the European Community (EC). In 2009 the EC’s institutions were absorbed into the EU’s wider framework and the community ceased to exist.

The EU became a trading bloc and the biggest market in the world, out competing with individual external nations such as the UK, such that by 1973 the UK government felt it necessary to join the EU to arrest its economic decline.

The UK certainly economically prospered after joining what is now the EU. Trade liberalisation, harmonised regulations, standardisation and tariff-free access to the huge single European market for exported and imported goods and services boosted UK production. The UK gained from EU direct investment. Increased competition has pushed companies to become more productive and forced British firms to increase the level of innovation, but many didn’t and so disappeared such as British Leyland and ICI.

By 2013, Britain became more prosperous than the average of the three other large European economies for the first time since 1965. But British commercial fishing all but collapsed in 1975.

Strand 3: NI Good Friday Agreement Must Remain Inviolable.

Northern Ireland’s Good Friday Agreement of 10th April 1998 has been critical to ending Northern Ireland’s centuries-old conflict and to enshrining a fragile perpetually inter-generational social peace.

Opposing soldiers of a lifetime – in peace earn a privileged moment

The agreement was approved by voters across the island of Ireland in two referendums held on 22 May 1998 and came into legal force on 2 December 1999. So like Brexit, the Good Friday Agreement is the will of the people.

The Good Friday Agreement comprises two inter-related documents – the multi-party agreement by most of Northern Ireland’s political parties and the international agreement between the British and Irish governments.

It sets out a complex series of provisions relating to a number of areas including:

- Strand 1: The status and system of government of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom,

- Strand 2: The relationship between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland,

- Strand 3: The relationship between the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom.

The agreement also created a number of institutions between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, and between the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom. Issues relating to sovereignty, civil and cultural rights, decommissioning of weapons, demilitarisation, justice, and policing were central to the agreement.

Ireland’s Tánaiste (Deputy Prime Minister) and Foreign Minister, Simon Coveney, in January 2018 wrote:

“The agreement removed barriers and borders – both physically, on the island of Ireland; and emotionally, between communities in Ireland and between our two islands.

The genius of the agreement is that it provides a framework for all of the relationships on our two islands – between communities in Northern Ireland, between north and south on the island of Ireland, and across the Irish Sea.

I am always struck by just how carefully woven together these relationships are, with each of the three interlocking relationships reinforcing the others.

Strengthen one, and you strengthen all; damage one and you damage all… No matter what else, Ireland-UK relations (must) not suffer as a consequence.”

The integrity of the Good Friday Agreement must remain supreme, intact and inviolable. Brexit must in no way endanger the Good Friday Agreement.

Strand 4: No Physical Border between Ireland and Northern Ireland.

No intra-Island of Ireland separation must ever recur as a physical border to divide the people of island of Ireland.

Reimposing a hard border is certain to unravel the still fragile Peace Process. To secure the trust of the people of the island of Ireland, any workable and sustaining Brexit must perpetually enshrine the inviolability of a borderless intra-Ireland. The Irish Government has clearly prioritised the preservation of the no-Border arrangement with the North as its “bottom line”.

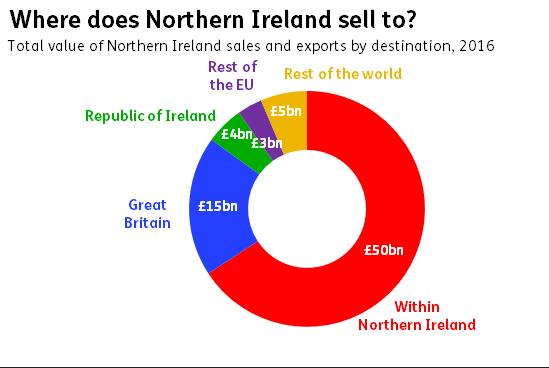

Strand 5: Brexit Must not Damage Ireland-UK Trade and Commerce.

The UK and Ireland economies are closely intertwined across many trade sectors, particularly in Agri-Food.

There are now more than 60,000 Irish-born directors on the boards of UK companies. The trading relationship is worth over £65bn a year, sustaining more than 400,000 jobs across both islands. The flow of people across the Irish Sea every day has made the Dublin-London air corridor the second busiest in the world. The UK-Ireland relationship is deeper, richer and more enduring than the issue of Brexit.

There are now more than 60,000 Irish-born directors on the boards of UK companies. The trading relationship is worth over £65bn a year, sustaining more than 400,000 jobs across both islands. The flow of people across the Irish Sea every day has made the Dublin-London air corridor the second busiest in the world. The UK-Ireland relationship is deeper, richer and more enduring than the issue of Brexit.

The Irish Times in 2016 reported that 30 per cent of Northern Ireland’s exports, about €2 billion, came south, whereas just 1 per cent of the Republic’s exports – which still amounted to €1 billion – went North. Irish farmers and dairies sell 100,000 tonnes of cheese to the UK every year while more than half of the Republic’s €2.5 billion beef exports go to the UK.

In July 2018, the head of Irish Creamery Milk Suppliers Association (ICMSA), Pat McCormack, said “the North-South trading relationship is much, much more important for Northern Ireland whereas for the Republic, and very specifically for the Republic’s farming and food production sectors, it is the west-east, Republic-to-Britain trading relationship that is our core economic concern.”

Business-as-usual trade north and south across the island must be unimpeded. Brexit must in no way endanger cross-border trade between the UK and Ireland.

Strand 6: EU Registered Identification.

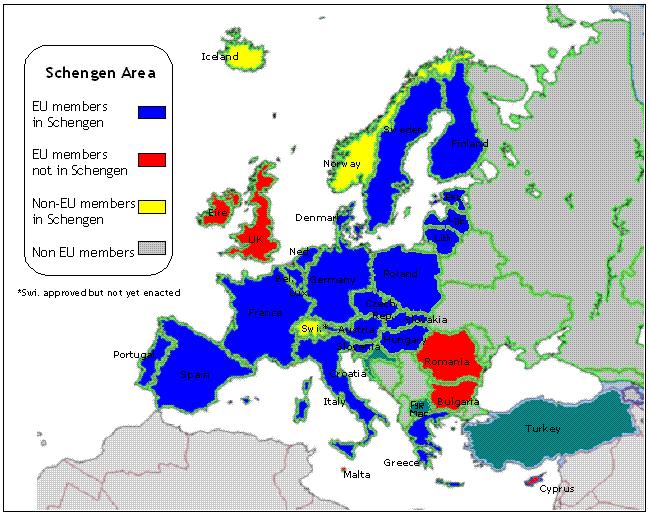

The European Union exists as an organisation for the benefit of its member countries as a single internal economic market and as a trading bloc with non-member countries – the rest of the world. Member countries – their businesses trading in goods and services, their financial capital, the Euro currency and EU citizens – are included in the common trade bloc, while non-member countries and their respective businesses, financial capital, other currencies and people are not included. EU member countries and non-member countries are mutually exclusive. There is to be no overlap. No dual EU-UK citizenship is to be available in order to avoid ambiguities and exploitations.

Businesses and financial institutions have their principal place of business geographically either within the EU or outside the EU, not both. The rules of the EU such as its Common Customs Code only apply to those inside the EU. The EU does not have any jurisdiction outside the EU.

It is incumbent upon the EU government (the ‘European Council’) to apply its own common rules as a bloc (common customs tariff and charges) externally to non-member businesses and financial institutions. Similarly freedom of movement within the EU only applies to EU citizens.

Non-EU nationals in general are subject to restrictions in relation to their freedom to reside, travel, work or study within the EU. For instance, visas, permits, conditions, quotas, time limits, and taxes generally apply to non-EU nationals within the EU. Special variations apply in respect to non-EU nationals who are direct family members of EU citizens.

Also the EU has special agreements with certain non-EU member nations such as Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway in which their nationals can work in the EU on the same footing as EU nationals, since they belong to the European Economic Area. For instance, workers from Croatia may face temporary restrictions on working in Liechtenstein. Otherwise specific bilateral agreements exist between the EU and other non-EU countries.

It is incumbent upon the European Council to identify and apply its external policies and rules to non-EU entities – businesses, people, currencies, goods, services and capital. This need not be at any physical border of the EU, but rather at the time of the business transaction and movement of people. This EU governance and application of its rules is not the responsibility of those outside the EU. So in the case of Brexit, the UK will not be responsible for governance and application of EU rules to the UK – its goods, services, capital and people.

Upon Brexit, the unique identifiers of EU membership of goods, services, capital and people will be deemed invalid – not-EU.

UK businesses that trade in goods and services with the EU will have their unique EU identifier (EU Value Added Tax number) invalidated, and will need to revert to a unique UK VAT number, thus subject to the same EU-tariffs as other non-EU countries.

Similarly, UK citizens will have their EU passports invalidated and revert to UK Passports, as subject to the same EU-restrictions of movement into and around the EU as other non-EU citizens.

The EU’s Capital Requirements Regulation which is directly applicable in all EU member countries prescribes the prudential requirements for capital, liquidity and credit risk for resident financial institutions within the EU.

The EU groups these institutions into Monetary financial institutions (MFIs – typically ‘banks’), Investment funds (IFs), Financial vehicle corporations (FVCs), Payment statistics relevant institutions (PSRIs) Insurance corporations (ICs). These each have unique European Investment Bank (EIB) identifiers. Upon Brexit, those residing in the UK will become invalid.

The governance and application of EU rules to the UK upon Brexit will ultimately be the task of the European Council, not the UK.

The UK was never being a member of the Eurozone, so there will be no adjustment to the UK’s currency, the Pound Sterling.

Strand 7: EU/Non-EU transactions of goods, services and financial capital to trigger EU rules, not the physical location of the exchange.

At each transaction of goods, services, and financial capital triggering EU-VAT that involves an EU entity and a non-EU entity, the EU common tariff is to apply. It incumbent upon the European Council to apply it – that is to apply its own external trade rules. EU internal transactions are of course exempt under the EU’s single market rules.

In order to critically avoid the need for any physical customs border between any EU member country and a non-EU country, it is the transaction and its timing that needs to trigger the EU tariff or otherwise applicable EU rules. Each transaction must be uniquely identified under EU rules to trigger the applicable EU tariff /tax rules. Technology and cooperation across the island of Ireland are key to effective implementation.

The European Council is responsible to devising how its tariffs and rules are applied and collected. In order to avoid a cash economy and black markets avoiding the EU tariffs and rules, it is incumbent upon the European Council to devise sufficient monitoring of businesses and financial institutions through tax profiling and audits to identify evasion of tariff/taxes and rules.

In the case of the Ireland/Northern Ireland border, the recognised non-sovereign border’s special status between the people of the Island of Irelands needs to be recognised by the European Union as a unique exception. This is because the no hard border was a democratic decision by the people of both the North and South.

In voting for the Belfast Agreement, Irish people, North and South, decided that, subject to the continuing consent of Northern Ireland’s voters, sovereignty over the north-eastern six counties should remain with the UK, even if people in the North can opt for British and Irish citizenship. No other borderless agreement exists between any EU member country and a non-EU country.

This special recognition is wholly consistent with the goals and values of the EU, notably to promote peace, offer freedom of movement, and respect representative democracy.

If, for example Denmark and Sweden were to vote to exit the EU, a hard border between sovereign nations between EU member countries and Denmark and Sweden respectively, unless a special non-border democratic process were to be undertaken.

Strand 8: Island of Ireland ports delegated to screen all non-EU citizens entering/leaving/transiting.

Border controls at the international ports of the Republic of Ireland and of Northern Ireland are best placed to screen all people movement to/from the island of Ireland – other EU member countries, as well as to/from non-EU countries (the rest of the world).

95% Muslim male workers

These existing international ports include airports and seaports. There is no land connection between the Republic of Ireland and any other sovereign country, with the unique exception of the country of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom.

The customs screening of all people movement at these ports – entry/exit/transit movement being to or from the island of Ireland – obviates the need for any hard border to exist between the South and the North of the island of Ireland. Critically, this sanctifies Strand 4: ‘No Physical Border between Ireland and Northern Ireland’ herein this document.

Harmonised joint co-operative customs screening by both North and South will serve to enhance border security for the island of Ireland. It will serve to better monitor the flow of visitors, migrants, goods and services, and prevent the smuggling of contraband, exploitation by black market criminality, and the flow of illegal entrants/workers/migrants.

Post Brexit, customs screening at these international ports will enable EU rules to be applied to non-EU citizens and their cargo. Although Northern Ireland international ports will not be subject to EU rules, the North must act as an agent for the EU in its customs screening and tariff charging.

The full cost of this EU agency function needs to be fully funded by the EU. Critically, by the EU border customs screening function being undertaking at the international port of Northern Irelands, this obviates the need for customs screening at a hard physical land border between Ireland and Northern Ireland.

Each person entering/leaving/transiting through any international port on the island of Ireland must be subjected to customs screening. This includes passport checks and visa checks. Each person must be required to hold a valid passport to pass through these ports, else be rejected, and held in detention and subject to deportation.

Relevant to the resolution of Brexit, a person’s passport will be either a citizen of the EU or not.

Upon Brexit, a UK citizen (which includes a Northern Irish citizen) will not be deemed to be an EU citizen, but a non-EU citizen (a UK citizen). UK citizens will compulsorily be required to hold a UK passport for customs identification for any travel internationally outside the UK, such as to the Republic of Ireland (an EU member country).

EU citizens travelling to the UK (including to Northern Ireland) will post-Brexit, be subject to the EU customs rules for outbound travel, as they may apply. EU citizens travelling to the UK (including Northern Ireland) will be subject to the UK customs rules for entry into the UK, as they may apply. The national passport held shall determine the rules applied in all circumstances as prevails specific to countries around the world.

Critically, citizens of the Republic of Ireland will automatically hold exemption to travel to Northern Ireland. Conversely, citizens of Northern Ireland will hold exemption to travel to Northern Ireland.

International travel by citizens of both the South and the North respectively outside the island of Ireland shall be required to hold a respective passport. A citizen of Northern Ireland will be required to hold a Northern Ireland passport. A citizen of the Republic of Ireland will be required to hold a Republic of Ireland passport.

Upon screening at any of the international ports on the island of Ireland, a holder of a Republic of Ireland passport shall be deemed an EU-member country citizen, whereas the holder of a UK passport shall not. The customs staff shall apply the relevant EU customs rules or UK customs rules as appropriate.

International traveller scenarios will need to be considered and rules drafted in order to capture loopholes and to prevent exploitation such as smuggling as well as unintended consequences.

Concerning the EU post-Brexit, the various types of people movements involving the UK, EU and NI involve various scenarios. These may be grouped into ‘EU Internal’, ‘EU External’, ‘EU Exception’ (NI-IRE), ‘EU Transits’ (multiple national migrations).

The following table of travel scenarios are intended to be instructive to reveal the complexity.

People Movement Scenarios:

A EU entry/exit UK

B EU entry/exit Rest of World

C EU entry/exit NI

D NI entry/exit Ireland

E UK entry/exit Ireland

F UK entry/exit NI

G Rest of World entry/exit NI/UK

H Rest of World entry/exit Ireland/EU

I Rest of World transit via EU

J Rest of World transit through NI to Ireland/EU

K Rest of World transit through Ireland/EU to NI

L Rest of World transit through UK to NI

M Rest of World transit through UK to NI to Ireland/EU

Etc.

In Brexit for each above people movement scenario, the UK and EU need to consider the visa type – holiday, working, migration, study, family reunion, humanitarian, temporary, seasonal, permanent, etc. The border risk for each combination scenario also needs to be considered and planned for.

Strand 9: Brexit Transition and Review Process.

The European Union’s expansion and complexity since the UK joined in 1973 has made the prospect of exiting complex and difficult, perhaps intentionally.

If Brexit was straight-forward, the process would have been long completed. Clearly, the first cut breakaway solution will expose problems – some predictable, others not so.

Flagged risks of Brexit highlight the economic trade interdependence between the UK, EU and the USA which risks being jeopardised by rash decision-making or neglect post Brexit. For instance, all of U.S. Foreign Direct Investment went to Europe in 2016, a quarter of which went to the UK. Multinationals from the U.S. are highly integrated across the Channel.

Clearly, the Brexit process should expect and plan for transitional arrangements to manage the relationship between the UK and the EU after the UK’s withdrawal from the EU.

There are real socio-economic concerns in the UK about a ‘cliff edge’ scenario with a rushed Brexit. There is an imperative that trade economics maintain a status quo for a transition time to limit disruption, and to maintain business investment certainty and consumer confidence.

Post–Brexit, trade bilateral negotiations need to replace the many complex EU agreements and these will take time and require a framework of trade negotiation and re-adjustment.

It is proposed that a transitional period should run from 29 March 2019, the date of the UK’s formal exit from the EU, until 31 December 2020. During this period, the UK would no longer participate in EU decision-making, but would “maintain … all the advantages and benefits of the Single Market, the Customs Union and EU policies”.

During transition, the UK seems to be bound by the EU’s international trade agreements.

But the EU has many hybrid agreements like with Norway, Iceland, Switzerland, Bulgaria, Romania and Croatia.

So the UK has many precedent special agreement options with the EU post-Brexit. The ‘soft’ or ‘hard’ Brexit propaganda out of Brussels is financial negotiation spin for an ignorant simpleton media.

There will be areas of formal agreement between the two parties, as well as areas of political agreement on which “further clarifications” are needed, and areas of continuing “disagreements or divergences”.

Topics yet to reach agreement thus far include:

- The land border between the UK and EU at the Irish border

- Governance of the agreement

- Geographical indications for food products

- Data protection

- Fishing catch quota negotiations

- Interpretation of EU retained law

- Automatic recognition of judgments by the Court of Justice of the EU

- UK entering into new trade relationships of its own with the EU.

Strand 10: Ireland’s European Union Status to Remain Unaffected by Brexit.

The Republic of Ireland’s membership and status within the European Union’s multi-nation single market for trade is to remain unaffected, except that when the UK exists, the 28 nations will reduce to 27.

Economically, the EU functions as one territory without any internal borders or other regulatory obstacles to the free movement of goods and services.

Membership access to the single market requires acceptance of free movement of goods, capital, services and people- – termed the Four Freedoms.

As a customs union, the EU applies common tariffs on imports from non-EU countries and can trade freely with each other without border checks. The Republic of Ireland trades freely with other EU countries.

Brexit must in no way endanger Ireland’s EU membership status, privileges and rights.

Brexit presents Ireland with dual geo-trade opportunities

Strand 11: EU to continue trading with the UK as a Non-EU Country.

Brexit logically necessitates the United Kingdom leaving the European Union and assuming trading status as a Non-EU ‘third’ country, just like America, Canada and Australia.

Non-EU export opportunities present. So what has Theresa being doing with her time?

The EU’s custom union will impose common tariffs on all import and exports between the UK (which includes Northern Ireland) and the EU. This will include common tariff rules such as import and export procedures, rules of origin, quotas, anti-dumping measures, border checks, etc. The UK will not have access to the free movement of goods, capital, services and people.

Brexit should be respected by all parties not as a negative snub but as a democratically expressed right to change international trading arrangements between the UK and the EU’s 27 member European countries – the EU27.

Rather than perceiving Brexit as a withdrawal to some trading vacuum, the goal needs to be positive and proactive to achieve a new trade agreement between the UK and the EU. It is a migration from one agreement to another with new terms.

Brexit presents no paradigm shift in UK-EU relations, rather a normal evolving re-negotiation in trading terms.

Mutual trade benefits desire the EU continues to trade with the UK all but business as usual with the UK status simply reverting to a Non-EU Country.

Strand 12: UK import and export standards for goods, capital, services and people to be EU-harmonised.

Brexit must not entail the UK abandoning established strict and ongoing compliance with EU Harmonised Standards across all trade sectors. EU Harmonised Standards set agreed benchmarks for the safety and quality of products and services across multiple trade sectors – in energy, healthcare, agri-foods, transport, etc. all designed to protect consumers and facilitate Intra-EU trade.

EU Harmonised Standards and UK Standards need to be also harmonised in order to ensure that UK-EU international trade be mutually trusted and accepted as valid throughout the UK and the EU across all the trade sectors and so reciprocated.

The Construction Products Regulation (CPR) lays down harmonised rules for the marketing of construction products in the EU. The Regulation provides a common technical language to assess the performance of construction products. It ensures that reliable information is available to professionals, public authorities, and consumers, so they can compare the performance of products from different manufacturers in different countries.

Since 1 July 2013, the CPR has required manufacturers to CE mark any of their products covered by a harmonised technical specification. CE-marking will not be mandatory anymore for EU products traded on the British market.

Conversely, British Standards Institution Kitemark will need to become mandatory, UK government regulated and harmonised with the EU’s CE Mark and so comply with applicable EU Directives so that UK products can be traded into EU Member States markets.

The British Standards Institution (BSI) will still be a voting member of CEN, like European Free Trade Association (EFTA) members and this must not change.

Trading with the EU, the UK will have to make a lot of concessions on their side and still have to comply with EU rules such as food standards and Food Contact Materials. EU regulations on food contact materials must be enshrined into UK law, to ensure the British public has the same level of protection after Brexit.

Strand 13: The UK to negotiate a Bilateral Agreement with each EU Member State.

The UK must ‘soft-Brexit’ by not joining the European Free Trade Association or the European Economic Area. This Norwegian model of dealing with the EU presents a fake Brexit that would engender business confusion across the UK and so risk economic chaos, and drive big business relocation out of the UK.

Democratic Brexit voted for UK sovereign trade, independent from the EU globalist common control out of Brussels.

The UK instead needs to negotiate separate bilateral agreements with each EU Member States. This is termed the “Swiss-model”.

Like Switzerland, the UK and EU will need to sign a Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA) or similar in order to prevent double conformity assessments.

Indeed a ‘Canada-style’ adopted trade arrangement would mean access to, but not membership of, the single market. Independence from a common market will necessitate some ogeous handlin’, but the EU is used to that and such is the nature of contemporary international trade.

But some simply stuff, because otherwise it’s too complicated to communicate let alone understand.

“I’ve been clear that Brexit means Brexit. I actually think I think better in high heels. My whole philosophy is about doing not talking. Do you like my EU chain? When’s Christmas?”

“I’ve been clear that Brexit means Brexit. I actually think I think better in high heels. My whole philosophy is about doing not talking. Do you like my EU chain? When’s Christmas?”

Strand 14: UK to Reap the Benefits of Brexit.

By leaving the EU, the UK will restore its sovereignty over its borders, banking, and economic decision making – taxation, financing, policies, indeed inaction to address economic downturns.

The UK will not be beholden to socio-economic and fiscal dictates imposed out of Brussels such as compliance with European Commission requirements and imposed austerity measures to prop up failing economies such as Greece, Portugal and Cyprus. Leaving Brexit will restore democracy in the UK.

The UK will financially benefit from exiting the EU by no longer being required to contribute to the EU budget, currently a net £8 billion per annum after deducting subsidies of £4.5 billion per annum.

The UK government has agreed on a transitional defunding arrangement and this needs to be the UK’s bargaining chip in the ongoing negotiations.

What has PM May been doing all the while? Negotiating Plan A1, A2, an EU appointment?

Demographic leadership quotas never exceed merit

Demographic leadership quotas never exceed merit

Strand 15: UK to Proactively Mitigate Brexit Risks.

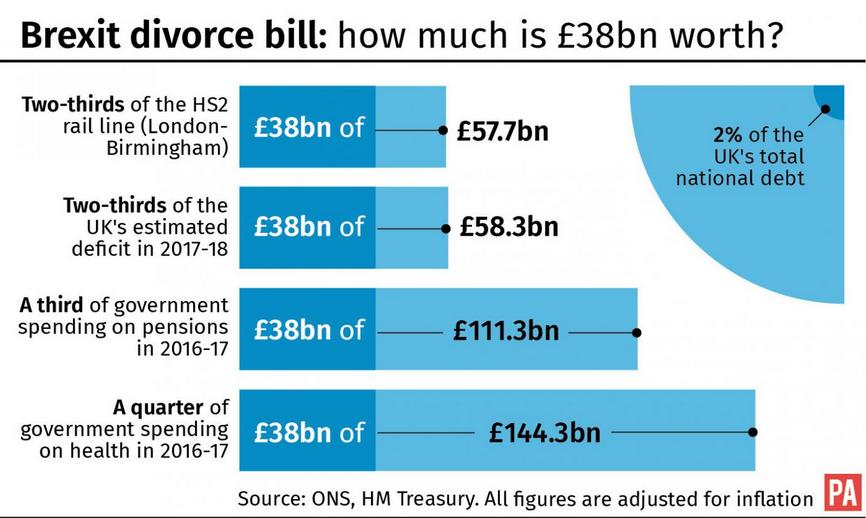

The UK’s initial perceived risk of Brexit is the so-called Divorce Bill debt figure of £38 billion being bandied around. But that’s according to estimates by Michel Barnier, the European Commission’s chief Brexit negotiator in Brussels – on commission no doubt.

But what’s conveniently included and excluded by Brussels here?

What about this conveniently excluded by Brussels?

It’s beyond Theresa May’s pay grade

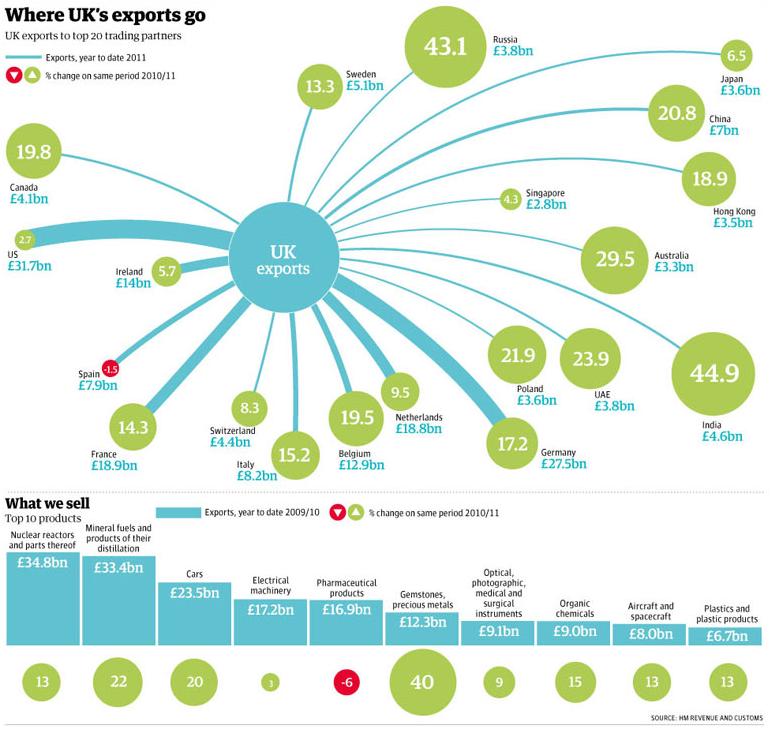

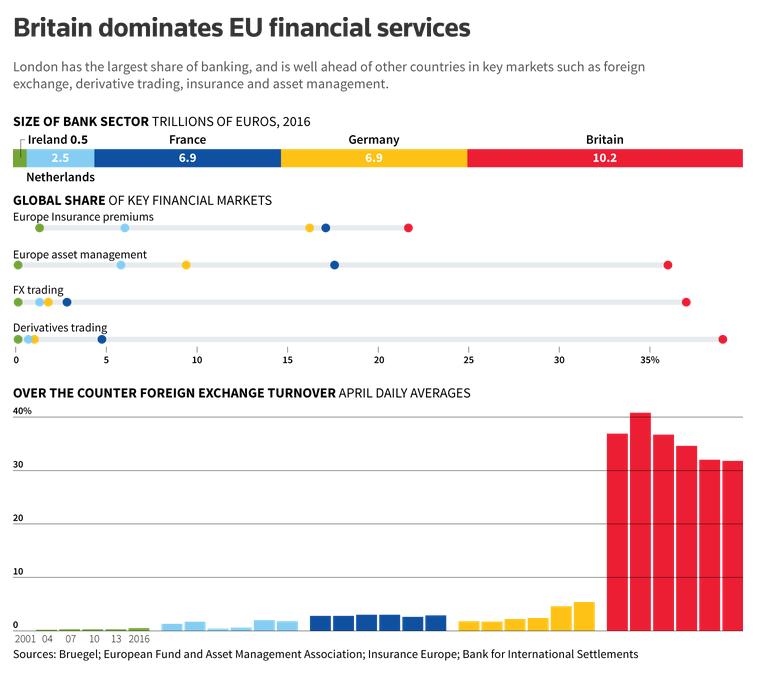

Maintaining the UK-EU trade is economically important for the post-Brexit UK. In 2017, UK exports to the EU totalled £274 billion or 44% of all UK exports.

Imports from the EU totalled £341 billion or 53% of all UK imports. Both UK exports and imports contribute around 30% of the UK’s GDP, so the EU trade portion for both UK imports and exports contributes to around 15% of the UK’s current annual GDP.

Notable is that the vast majority of small and medium-sized UK businesses do not trade with the EU, yet are restricted by a huge regulatory burden imposed from abroad. This burden needs to be addressed in the UK’s favour.

Yet continuance of tariff free trade between the UK and EU remains important for the UK to maintaining its EU-trade contribution the UK economy if even from a market/media confidence perspective.

By the same token, it is wise for the UK during the Brexit Transition that tariff free trade between the UK and EU is secured by the UK re-joining the European Free Trade Association and proactively negotiating bilateral agreements with the EU Member States, as proposed previously.

It would be foolhardy for the UK Government to staidly wait post-Brexit for new trade to flow out of nowhere arranged. In order for the UK to mitigate its economic over-dependency upon the EU, the UK needs to proactively negotiate new bilateral agreements with the rest of the World.

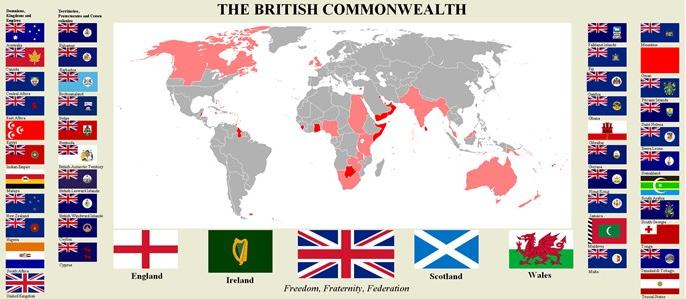

Most obviously the UK should capitalise upon it historical socio-cultural ties with its compatible First World former colonies – the United States, Canada, Australia, Singapore, New Zealand, and South Africa.

Other strong, growing and emerging international markets beckon. The UK Government needs to pull its proverbial finger out else embrace a naïve self-inflicted recession.

If the incumbent UK Government delegates think they might lack the requisite international trade skilling, then reach out to proven professional Brits suitably credentialed and trade-skilled to advise government, to accept ownership in the negotiated risks, but no less professionally project manage the new trade strategy.

Brexit campaigner Boris Johnson should be invited to lead Brexit negotiations.

Strand 16: UK to Re-establish a Commonwealth Trading Bloc to effectively compete against the EU Bloc.

When the UK decided it was in its economic interests to be pressured into joining the dominant EU trading bloc in 1973, the UK was forced to relinquish deep ancestral trade ties with former colonies of the British Commonwealth.

Prime Minister Edward Heath (1970-74) was optimistic that Britain’s membership of the European mainland community would bring temporal prosperity to the UK by being part of the world’s then largest trade bloc. It was a temporal relationship – one sided and not in Britain’s favour in the end.

These days, the EU’s fortunes have waned and have become a socialist empire allowing millions to economic migrate for welfare. British imports from Commonwealth countries are declining. In 1999 almost 12 per cent of all Commonwealth exports ended up in Britain. By 2015, that had dropped to less than 5 per cent.

Brexit presents the opportunity for a socio-economic renaissance to reinvigorate the Commonwealth as a trading network, leveraging a common culture, language and First World standards.

The Commonwealth’s 53 members have a combined population of more than 2.4 billion people but it is not at all clear that the UK wants what most Commonwealth countries have to offer, and vice versa.

Canada is part of the North America Free Trade Agreement but that is unravelling.

Australia’s largest trade partner is China, accounting for about 23 per cent of total trade, but China’s import dumping has decimated Australian manufacturing and industry.

The UK’s Brexit transitional trade arrangements set likely to be in place by 2019, allowing UK trade negotiators to turn their attention to, in order of priority, the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Reinvigorate the Anglosphere

‘Regardless, abroad we all know our ancestry…